Upper Caroline Neighborhood History

Researched by Jan Waltonen & Roger Engels, HFFI Marker Committee

Written by Jan Waltonen

Article compiled for the 2019 Candlelight Tour. Properties on the tour included the Rising Sun Tavern, 1308, 1309, 1310, 1513, and 1517 Caroline Street.

This year’s Candlelight Tour (CLT) explores a neighborhood whose history began more than a hundred years before the American Revolution. Before about 1779, “Land Patent” documents conveyed land in the royal colony of Virginia from the colonial governor in Williamsburg—in the name of the King of England—to individuals who could pay their passage to America. This “headright” system rewarded persons with 50 acres of land if they sailed to Virginia to “inhabitate.” However, if new immigrants could not afford to travel to Virginia, others could finance the cost of transporting them, receiving 50 acres for each person they imported. Designed to attract colonists to Virginia to work for its benefit and provide revenues for the Crown, the system successfully encouraged settlement and increased the colony’s population. Both Fredericksburg and the area encompassing this year’s Candlelight Tour owe their beginnings to the Land Patent system.

In 1662, a large Land Patent of 812 acres was granted to Captain Thomas Hawkins, a close friend of the earliest Washingtons, who paid to transport 17 persons to Virginia. Seventy years later, Hawkins family descendants sold their Patent in two equal parts. The 406 acres that Francis Thornton of King George County purchased extended north from Lewis Street—the original boundary of Fredericksburg—to present-day Hunter Street, embracing all the properties on this year’s CLT.

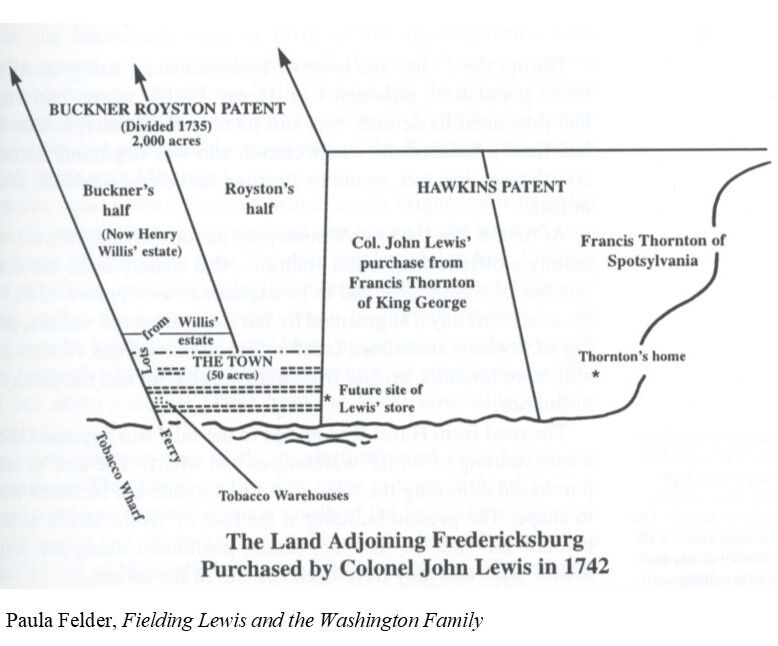

Seven years later, in 1742, Colonel John Lewis (1694–1754) bought the Thornton “half tract” for £500. Lewis’s purchase, adjoining the upper end of town, supported his new and ambitious business enterprise. As a prominent merchant, he was shipping goods to the West Indies, London, and other trans-Atlantic ports. Within 1 year of acquiring the Thornton tract, Lewis had built and was operating a store, warehouses, and a shipyard, all located at the site of the present-day Fredericksburg Library. To oversee the mercantile extension of his shipping business, he enlisted his second son, Fielding, and in 1749, built the Lewis Store on the west side of Caroline Street just outside the town line. (Today, the Lewis Store, one of the oldest surviving urban retail stores in the United States, is headquarters for HFFI.) As the store’s manager, Fielding Lewis sold items such as rum, buttons, gloves, sugar, coffee, “brest” buckles, and “soop” spoons. His customers included George Washington, who, in a letter to his mother, requested she buy cloth, hose, and thread for him from “Mr. Lewis’s store.”

Although all this year’s CLT properties lay outside the corporate limits of Fredericksburg in Spotsylvania County before 1759, several factors fueled Fredericksburg’s growth and expansion to include new land. Founded in 1728 as a shipping port, Fredericksburg became an important center of trade. Ships brought European goods for sale in local stores, and tobacco, the basis of Virginia’s economy, was exported to England and Europe, solidifying Fredericksburg’s prominence as a center of commerce. Owing to its standing as a major port and seat of justice, the fledgling town grew rapidly. In 1759, to accommodate the burgeoning population of merchants and tradesmen, court justices, tavern keepers, and enslaved and free blacks, the Virginia General Assembly expanded the town limits to include present-day Dixon, Winchester, and Canal streets—bringing all of this year’s CLT properties within town limits.

A beneficiary of Fredericksburg’s prosperity was merchant Fielding Lewis (1725–1781). By 1754, the year his father died, Fielding had amassed an estate of 1,300 acres, including the Thornton tract he had inherited. It was said he owned “half the town” in the days before the War for Independence. In 1775, on the eve of the Revolution, he and his second wife, Betty, George Washington’s sister, moved into their newly constructed Georgian mansion (now called Kenmore). Lewis, a patriot of the American Revolution, established a weapons factory in Fredericksburg. By May 1777, the Gun Manufactory was producing about 20 muskets weekly. Lewis spent £7,000 of his own money, which was never repaid, leaving the family to struggle financially after the war.

When Lewis died in 1781, his son John inherited not only his father’s lands in Fredericksburg but also his substantial debts. To pay them down, John sold three town lots in 1785 to Henry Fitzhugh of Bell Air, Stafford County. Lot 178, site of two of this year’s CLT homes, marked the northernmost boundary of Fredericksburg and was considered a “suburb” of the town. (The term “suburb” was commonly used then as now to refer to an outlying part of a town or city.) In the early nineteenth century, a number of planned suburbs were laid out on the fringes of Fredericksburg and named after the land speculators who developed and financed them. Henry Fitzhugh, member of one of the “first families of Virginia,” was among those investors. He divided his new acquisitions into residential lots, naming the area “Fitzhughtown” after himself. Two houses on this year’s Candlelight Tour, 1513 and 1517 Caroline Street, are on Fitzhughtown lots. By 1787, Fitzhugh was renting his land to “sundry free Negroes and whites.”

The 1300 block of Caroline Street was also under development during the late eighteenth century. In 1761, Warner Lewis, Fielding’s older brother, sold George Washington’s younger brother, Charles, the lots where Charles would build his private residence in 1762. Thirty years later, the building was sold outside the Washington family and converted to a tavern. Today, Washington Heritage Museums operates the Rising Sun Tavern as a living history museum to showcase Fredericksburg’s colonial history.

Upper Caroline continued to develop as a diverse neighborhood in the 1800s. The United States Censuses are organized in order of households visited. The 1860 Census reveals that individuals working as shoemakers, “washwomen,” plasterers, weavers, and stone masons lived side by side with more affluent residents: a carriage maker, barrel maker, “loom boss in a factory,” and a dry goods merchant.

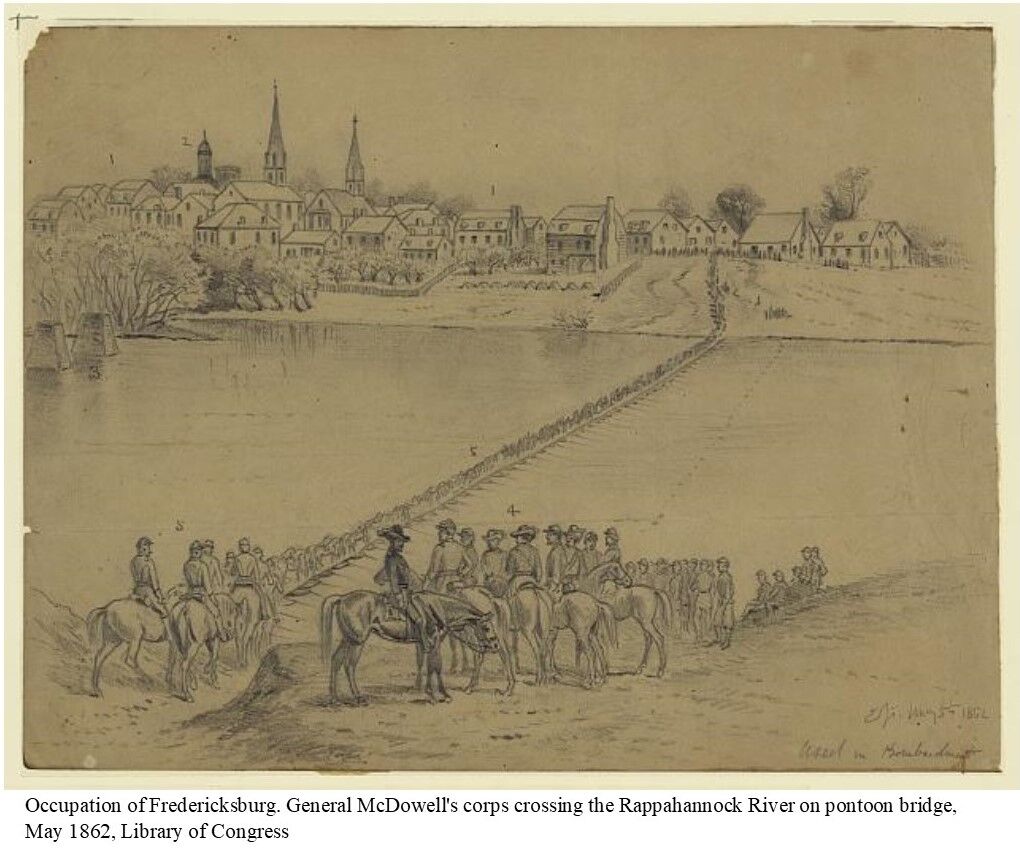

The impact of the Civil War on the upper Caroline neighborhood was devastating. On December 11, 1862, Union engineers attempted to build three pontoon bridges. The northernmost crossing site terminated at Hawke Street, just one block south of this year’s CLT properties. Ordered to delay the Union troops, General William Barksdale’s Mississippi riflemen, positioned along Sophia Street, fired on the bridge builders, preventing them from completing the northern pontoon bridge. Union commanders responded by ordering a massive artillery bombardment. The shelling of Fredericksburg destroyed about 100 structures—10% of the city. Two beams in the Rising Sun Tavern’s roof were cut through by artillery fire.

Despite the fire of 150 cannons, the Mississippi sharpshooters, entrenched in cellars and doorways, could not be dislodged. Union infantry finally crossed the river and ultimately cleared away the snipers, although they fiercely contested every block. Among the streets most closely associated with the street fighting were the streets on this year’s CLT—Fauquier, Hawke, Pitt, and Canal. The cost was great. In gardens and backyards, graves of the dead were scattered across the city.

The area comprising this year’s CLT was also hard hit with indiscriminate destruction and looting the day before the Battle of Fredericksburg. Argalus E. Samuel, a carriage maker owned the lot on which 1513 Caroline now stands. He was just one of several residents who filed “A Memorandum of Losses in the Shelling & Since” with the Common Council of the town, which passed the following resolution on January 10, 1863: “Resolved that the funds now being raised by the voluntary contributions of the Army for the relief of the citizens of Fredericksburg who have suffered so severely by the bombardment & sacking by the abolition Army shall be received and disbursed. . .” Receipts collected totaled a remarkable $32,292.60. Samuel’s inventory of losses included “provisions on hand and groceries stolen” worth $96.60—much more than the value he placed on any of his furniture or even his “working tooles” [sic].

The war continued to be a harrowing experience for A.E. Samuel. Following the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864, about 60 Union soldiers—many slightly wounded—made their way to Fredericksburg, seeking to return to Union lines. Placed under citizens’ arrest, they were sent to Richmond as prisoners of war. In retaliation, federal authorities arrested a corresponding number of local citizens to be held as hostages until the Union soldiers were released and returned. Samuel was one of 57 men sent to the military prison at Fort Delaware. After 3 weeks, Fredericksburg’s mayor and Common Council sent an appeal to the Confederate Secretary of War in Richmond: “Surely the matter of a few [federal] prisoners cannot be allowed to interfere with the humane and generous work of restoring to those desolated homes and those mourning women and children, the only source of comfort in this war-ravaged and desolated town. . .” Samuel was subsequently exchanged in July, only to find that his sister had died during his imprisonment.

After the war, Fredericksburg’s residents were left to rebuild in a shattered economy. It took nearly a generation for the town to begin to prosper again. The houses on this year’s CLT—built between 1870 and 1911—echo that slow recovery. They illustrate not only Fredericksburg’s eventual renewal but also the contrasts that came to define Upper Caroline’s character. 1513 Caroline, constructed shortly after the war in 1870, was built for James Ryan, an Irish immigrant and stone mason. Assessed at only $350.00 at the time, it represents the many post-war working class residences of this diverse neighborhood. In contrast, in 1911, the Victorians at 1308 and 1310 Caroline were built by G.B. Wallace, a prominent Fredericksburg citizen who served as the Commonwealth’s Attorney for 20 years. These three CLT properties symbolize the wide diversity of architectural styles and residents’ socio-economic levels, offering a vivid glimpse into a rich history. Welcome to Upper Caroline!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!