A Closer Examination of Historical Significance: The Charles Dick House and J.W. Masters’ Domestic Outbuilding at 204 Lewis Street

Written by Danae Peckler (with gratitude to Fredericksburg history lovers and preservationists from generations past and present who have made it easier to research and learn from all that surrounds us)

Although the structure at 204 Lewis Street was built between 1910 and 1912 for local lumber dealer John W. Masters (1854–1929), it is more closely associated with the history and development of the property known as the Charles Dick House at 1107 Princess Anne Street than many realize.

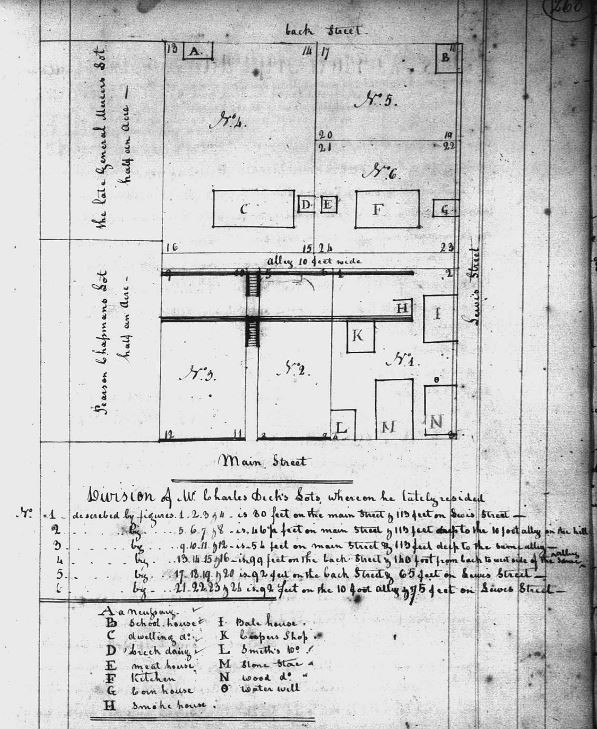

Charles Dick is believed to have purchased Lot No. 52 about 1750, adding to his holdings at Lot 51, where he owned and operated a store (Johnson 1992). The house he built on Lot 52 faced the river and was accessible by two terraced staircases from Dick’s place of work at the southwest corner of Caroline and Lewis streets. The relative positions of these features and various buildings on Dick’s property are shown in a 1786 plat dividing his estate for sale at public auction (Figure 1). Little historic fabric survives from Charles Dick’s tenure on this property save the stone retaining wall—a portion of which required emergency stabilization in 2019 (Figure 2). However, the boundary lines created for the 1786 sale also remain on the landscape today. According to James Mercer’s survey, the three lots created along Caroline Street extended west 113 feet to a 10-foot-wide alley at the top of Dick’s second terrace and 182.5 feet along Caroline Street. Today, all the parcels from 1114 to 1124 Caroline are 114 feet deep and a total of 181.4 feet wide (City of Fredericksburg Deed Book A, p. 268; FredGIS 2022). Thus, a relatively accurate comparison can be made by overlaying the 1786 plat with modern satellite imagery (Figure 3).

But this is ancient history—what about that building to be demolished, you say? Although the physical fabric of this structure largely dates from 1911–1912, images of the Sanborn Fire Insurance Company maps from 1891 (Figure 4) and 1896 depict two other outbuildings around the same location. The colorized Sanborn maps reveal two adjoining frame buildings in the center of the block on the south side of Lewis Street: a one-story, rectangular stable (denoted by an “X” over the building—not to be confused with any specific kind of roofline) and a one-and-a-half-story building with a one-story lean-to addition that appears to have served as a dwelling at that time.

Overlaying these 1890s maps with the 1786 division plat and current satellite imagery provides additional insight into the lot’s history. The one-story building filled the northeast corner of Dick’s 10-foot-wide alley, while a second rectangular, one-story stable appears south of it along the west side of the alleyway. Other one-story outbuildings lined the northern boundary of what is now the parcel at 1107 Princess Anne Street, including a rectangular frame building labeled as “sheds” in the 1896 Sanborn map.

Figure 1: Copy of 1786 plat of Charles Dick estate, Created by James Mercer, executor, when dividing the property for sale (City of Fredericksburg Deed Book A, p. 268).

Figure 2: View of retaining wall below the Charles Dick House from Caroline Street, Image taken April 2021.

Figure 3: Overlay of the 1786 division plat of Dick’s estate with modern satellite imagery (Google Earth 2022; Johnson 1992).

Figure 4: Detail of 1891 Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. map showing 1107 Princess Anne Street property and its immediate surroundings, Fredericksburg, Virginia (Google Earth 2022; Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. 1891).

The 1890s maps depict the property during the ownership of William A. Little, an attorney at law then practicing with his son, William A. Little, Jr., from an office at the corner of William or “Commerce and Prince Anne” streets (Fredericksburg Directory, 1888–89). The property changed hands in 1901 and again in 1908 before it was sold to J.W. Masters by deed of October 25, 1910 (Johnson 1992). The same group of outbuildings described above appears in the 1902 and 1907 Sanborn maps. At that time, the dwelling adjoining the east side of the stable along Lewis Street had become a “stable” and a small, one-story frame shed was constructed in the middle of Dick’s alley, closer to the house (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Detail of 1902 (left) and 1907 (right) Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. maps showing 1107 Princess Anne Street and surrounding properties (Google Earth 2022; Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. 1902, 1907).

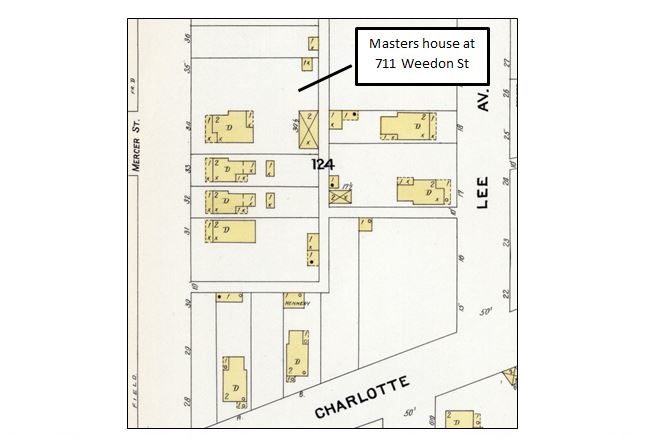

When they bought the Princess Anne Street property in 1910, Masters and his family resided in the old fairgrounds neighborhood on Weedon Street, opposite the intersection with Mercer Street—what is today the property at 711 Weedon Street. John William Masters (1854–1929) and his Fredericksburg-born wife, Ada Byron Chisholm (1861–1924), wed in 1892 and lived at 1303 Washington Avenue before relocating to the newly constructed dwelling on Weedon Street a few years later (1900 Census; Fredericksburg Research Resources, newspaper search).

Their house on Weedon still stands, along with a two-story “stable” that shares some architectural similarities with the outbuilding at 204 Lewis Street (Figure 6 and 7). The property at 711 Weedon Street first appears in a 1907 Sanborn map with the characteristic “X” denoting the extant outbuilding as a stable, although some called such structures “carriage houses” given their multi-functional roles sheltering a carriage/wagon, horse(s), and tack at the lower level while providing residential space above for servants such as a driver or groom (Figure 8). No servants were recorded in Masters’ household in the 1910 population census, but an African-American “driver” named Albert Parker appears in the local city directory published that same year residing at the Masters address (Fredericksburg, Virginia, City Directory, 1910–11).

Figure 6: View of the Masters property at 711 Weedon Street, showing the “carriage house” or “stable” behind the main house that likely doubled as the residence of the family’s driver Albert Parker.

Figure 7: View of 711 Weedon Street property from alleyway showing the stable’s Queen Anne styling in the use of asymmetry and differing textures on the exterior. The shingled projection along the north elevation of this outbuilding contrasts with the plain, unadorned, elevation along the back alley.

Figure 8: Detail of 1907 Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. map showing 711 Weedon Street with “stable” along rear alley (Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. 1907).

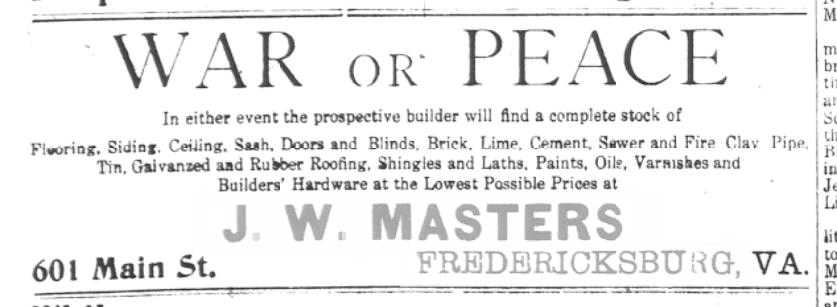

The year before purchasing the Princess Anne Street property, J.W. Masters erected a large new office and warehouse for his lumber business on Main Street (Caroline Street) and operated a planing mill on Wolfe Street—both of which are no longer extant (The Free Lance, April 3, 1909). Masters’ office was located at 601 Caroline (now the location of the “big ugly”), and his planing mill was located at 326–330 (now a parking lot) (1910–1911 City Directory, Stanton 2014). Masters was one of Fredericksburg’s largest lumber dealers around the turn of the twentieth century. His advertisements demonstrate the scope of his business in the local construction industry, displaying a wide variety of buildings materials (Figure 9).

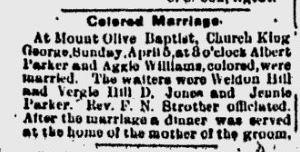

When the Masters family relocated to the Charles Dick House about 1912, Albert Parker appears to have moved with them. The 1920 population census reported Parker (then identified as a 25-year-old widower and erroneously labeled “white”) and another young African-American, Sarah Carter (age 17), working as “servants” and living on the Masters’ property (1920 Census; Fredericksburg, Virginia, City Directory, 1921). It is possible that this Albert Parker is the same man who reportedly married Aggie Williams in 1903, but that would indicate that the 1920 Census taker also underestimated his age—a fairly common occurrence in census records for people of color (The Daily Star April 8, 1903) (Figure 10). Parker and Carter likely resided in the circa-1912 outbuilding at 204 Lewis Street, giving greater privacy to the Masters family—a similar arrangement to the carriage house and quarters they had previously built at 711 Weedon Street. J.W. Masters and his first wife Ada died in the 1920s, but 1107 Princess Anne Street remained in the family into the late 1970s, passing from their children (Dr. Howard R. Masters and Ada Masters Gibson) to their granddaughter, Ellen Ross Gibson (Johnson 1992).

Figure 9: Advertisement for J.W. Masters (Northern Neck News, May 11, 1917).

Figure 10: Notice of Albert Parker’s marriage to Aggie Williams

(The Daily Star, April 8, 1903).

While much remains to be learned about the lives of Albert Parker, Sarah Carter, and other domestic servants the family employed, what we see at 1107 Princess Anne today is a reflection of J.W. Masters’ tenure and work to update the property in the early twentieth century. Between 1912 and 1919, Masters reoriented the house to face Princess Anne Street by adding the two-story, Neoclassical style porch that lines its west elevation, removing several additions and older outbuildings to enable smoother passage of vehicles through the property, and constructing a stylish new carriage house (Figure 11).

As one of few twentieth-century outbuildings designed in part as “servant quarters,” this unique dwelling has been maintained and repaired by subsequent property owners, providing much-needed residential rental space in our community for more than a half century. Outbuildings of this size, style, and type are not common survivors in Fredericksburg’s National-Register-listed historic district (or even in the expansion area repeatedly determined eligible for NRHP listing by the state historic preservation office). After travelling most alleys in town, Masters’ two examples remain the only two-story carriage houses from the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century identified.

Figure 11: Detail of 1912 (left) and 1919 (right) Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. maps, reflecting alterations made during the tenure of J. W. Masters in the early-twentieth century at the 1107 Princess Anne Street property (Google Earth 2022; Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. 1912, 1919).

Preserving this resource and other quirky buildings like it in our community is one of the best ways to protect our distinctive historic character and explore the kinds of diverse stories about our historic landscape. If we are to lose historic buildings that contribute to Fredericksburg’s unique built environment, then let it be through a careful, defined, substantive process that explores all options, prudently considers alternatives for repair and adaptive reuse, and respects the centuries of inhabitants who have left our community with a heritage so rich.

The application put before the ARB at its May 9, 2022, meeting was jam-packed with information but was light on substantive details to illustrate a good-faith effort to adhere to the goals and policies outlined in the district guidelines, which strongly discourage demolition of a contributing historic building (Chapter 12, Section B, City of Fredericksburg 2021).

The ARB is revisiting this application at the upcoming June meeting, which provides some time for reflection on the process and the existing data, further consideration of important questions, and reason to expect a more complete application in this second hearing. Let’s hope it allows for fair consideration of the facts from a broader perspective and permits the ARB to uphold its guidelines for demolition:

An on-site review by ARB members is required prior to any determination that a building or structure no longer presents an opportunity for feasible rehabilitation. As part of this process, a thorough structural analysis must be undertaken by a licensed structural engineer experienced in historic preservation work. Thorough documentation will be required of any building to be demolished; long-term neglect is not considered an adequate reason to demolish an existing building. City staff, HFFI, and other community partners may be able to direct property owners to resources to assist with maintenance and adaptive reuse.

Information that would substantially contribute to this discussion includes additional data on existing conditions at the 204 Lewis Street building and its historical context. If the ARB weighs this case using the “seven criteria for evaluating demolition” outlined in the district guidelines, it is hoped that this article can assist in better understanding the building’s architectural and historical significance (Criteria 1 and 2). It expands on the ways that modest outbuildings relay information about the economic, social, and political situations of lesser-known Fredericksburg residents such as those who labored as domestic servants in the early twentieth century.

This narrative might also shed light on how any such “structure is linked, historically or architecturally, to other buildings or structures, so that their concentration or continuity possesses greater significance than the particular building or structure individually” (Criterion 3). The high-style architecture surrounding this outbuilding largely dates from the first half of the nineteenth century when Princess Anne became a fashionable address and domestic servants, primarily enslaved, lived and worked in basements, rear ells, and back yards. West of 204 Lewis Street is a rear ell built between 1819 and 1820 in conjunction with the house at 1111 Princess Anne Street for William Brown (City of Fredericksburg Deed Book F, p. 393). Brown’s servant quarters filled the upper story of the ell with a kitchen on the first floor and a cellar below. In contrast, Masters’ twentieth-century servant quarters put greater distance between the family and their staff, yet continued to combine this space with another purpose using architecture. The location of Masters’ outbuilding also reflects the continued use of Dick’s alley as a passageway and Lewis as a side street. As such, the function, location, and architectural fabric of this structure provide a dynamic illustration of both change and continuity over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth century.

Finally, perhaps this article can illuminate how seemingly simple, accessory structures relate to preservation goals of the Comprehensive Plan (Criterion 4), specifically the need to balance the evaluation of a building’s cultural significance with its architectural conditions to “avoid undervaluing buildings associated with underrepresented communities due to modest design or limited physical integrity” (Chapter 8, Goal 4, Policy 4). Our cultural landscape, our historic district, the heritage tourists who visit our historic town, and Fredericksburg residents (past, present, and future) deserve no less. A good-faith effort from the participants in this process and those involved with future demolition applications of historic buildings in the district would include:

Demolishing any historic heritage asset in our community should be a measured and thoroughly deliberated decision, one that carefully examines facts—not one that rushes to judgment with limited evidence.

References:

City of Fredericksburg

2021 Chapter 12, Section B. Fredericksburg Historic District Guidelines. Fredericksburg City Council, adopted July 13, 2021. Electronic document, https://www.fredericksburgva.gov/DocumentCenter/View/333/Historic-District-Handbook?bidId=, accessed April 2022.

Daily Star, The [Fredericksburg, Virginia]

1903 Local notes on J.W. Masters new office and warehouse. April 8, page 3. Electronic document, https://news.google.com/newspapers, accessed May 2022.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Company

n.d. Sanborn Fire Insurance Company mapping, misc. years. Fire Insurance Maps online (FIMo), Library of Virginia, Richmond. Electronic database, https://fims-historicalinfo-com.ezproxy.virginiamemory.com/FIMS.aspx, accessed May 2022.

Fredericksburg Research Resources

2022 Fredericksburg Newspaper Search. University of Mary Washington Department of Historic Preservation. Electronic database, http://umwhispresc.wpengine.com/newspapersearch/, accessed April–May 2022.

Fredericksburg, Virginia, City Directory

1888 Chataigne’s Fredericksburg and Falmouth City Directory, 1888-’89. Copy on file at Central Rappahannock Regional Library, transcribed by Dr. Gary Stanton. Electronic document, http://resources.umwhisp.org/Fredericksburg/1889directory.htm, accessed May 2022.

1910 Fredericksburg, Virginia, City Directory, 1910–11, Vol. 1. Copy on file at Central Rappahannock Regional Library, transcribed by Dr. Gary Stanton. Electronic document, http://resources.umwhisp.org/Fredericksburg/1910directory.htm, accessed April–May 2022.

1921 Fredericksburg, Virginia, City Directory, 1921. Copy on file at Central Rappahannock Regional Library, transcribed by Dr. Gary Stanton. Electronic document, http://resources.umwhisp.org/Fredericksburg/1921directory.htm, accessed April–May 2022.

FredGIS

2022 Tax parcel data. City of Fredericksburg Geographic Information System. Electronic database, https://www.fredericksburgva.gov/515/Geographic-Information-System-GIS, accessed May 2022.

Free Lance, The [Fredericksburg, Virginia]

1909 Local notes on J.W. Masters new office and warehouse. April 3, page 3. Electronic document, https://news.google.com/newspapers, accessed May 2022.

Google Earth

2022 Google [computer program], satellite imagery. Electronic software, http://www.google.com/earth/download/ge/agree.html.

Johnson, John

1992 Historic Marker Report, 1007 Princess Anne Street. Copy on file at Historic Fredericksburg Foundation, Inc., Fredericksburg, Virginia.

Northern Neck News [Warsaw, Virginia]

1917 Advertisement for J.W. Masters. May 11, page 1. Electronic document, https://news.google.com/newspapers, accessed May 2022.