Fredericksburg’s 2024-2025 Goals for Preservation

For generations, Fredericksburg residents have taken pride in learning, sharing, and retelling tidbits of the extraordinary history our city holds. Many might recall that we once proclaimed ourselves to be “America’s Most Historic City.” An ambitious moniker that might sound audacious and pompous to some, yet we need only spend some time at local historic sites or read about the notable individuals and events that have put FXBG “on the map” for a few centuries now.

Other places have their own important history, but what TRULY sets Fredericksburg apart from the majority of localities is our community’s decades of dedication to Historic Preservation—the act of preserving the physical tangible evidence of our unique past.

Fredericksburg was a national leader in preservation in 1891 when a group of residents saved Mary Washington’s house from dismantling; in 1922 when efforts were made to save one of the finest examples of early American plasterwork; in when 1955 when Historic Fredericksburg was created to save an antebellum kitchen outbuilding; in 1972 when our historic district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places; in the 1980s when the nation’s first undergraduate program in Historic Preservation was established at what is now the University of Mary Washington; in 1991 when Fredericksburg was one of two localities selected for study in a ground-breaking economic analysis on the financial impact of historic preservation across the community; in 1996 when Ferry Farm was saved from being turned into a Walmart; and in 2021 when an archaeological ordinance more than a decade in the making was adopted.

Preserving the City’s cultural legacy—the historic buildings, sites, stories, and places, big and small, elaborate and commonplace—is a choice. It’s what we choose to do in Fredericksburg and our elected representatives are preeminently charged with caring for this tangible inheritance from the past.

As another Historic Preservation Month draws to a close, HFFI’s Board of Directors has laid out some important goals for the coming year—many of which are familiar to those with local leadership experience. By May 2025, we hope to report that these goals have been met. A full description of these goals is spelled out in HFFI’s press release (at bottom of post) with an abbreviated list below:

- Establish a Preservation Advisory Committee—Outlined in the City’s 2021 Preservation Plan, listed among Council’s top priority tasks that same year, and more recently proposed by the City’s Preservation Planner, this standing advisory committee would provide local preservation insight, expertise, and additional resources to carry out several City preservation goals. HFFI will work with the City to provide needed support and network with professional preservationists in the community to accomplish the goals of this committee.

- Conduct a Historic Preservation Economic Impact Study—It is important that the community and its leaders are aware of the significant and far-reaching economic impacts generated by the preservation of the City’s historic character and diverse built environment, including its direct and indirect benefits. Last summer, the National Park Service released an economic impact study of the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park that found its visitors spent $49.9 million in surrounding communities in 2022 alone. Funding for this kind of study was requested by City staff and the Planning Commission last fall. It did not make the FY2025 budget and was recently struck from a list of potential state grant applications. HFFI will work with City staff, the EDA, EDT, Main Street, Chamber of Commerce, cultural historic sites, and other organizations to make this longstanding goal come to fruition. We hope we can count on City Council’s support in the future.

- Implement Incentives for Preservation—Daniel Becker’s expert Recommendations report, completed in June 2023,outlined several potential incentives to fulfill one of City Council’s priority goals for Historic Preservation. The EDA and Council were briefed on this study last summer. We will work to support the City in acting upon those recommendations.

- Implement the 2012 MOU between City and HFFI—In 2012, a Memorandum of Understanding was established between the City and HFFI following years of proactive discussion and collaboration to improve the community’s response to decaying and blighted buildings. Several of the tasks and goals therein were reiterated in the June 2023 report on Economic Incentives and Prevention of Spot Blight and Demolition by Neglect. In the next year, HFFI will work toward implementing some of those tasks to assist property owners in and around Fredericksburg’s historic downtown core that are affected by blighted resources. We will coordinate with City Planning and Public Works staff in our efforts and expand the community’s support network for preserving our existing building stock, especially its residential resources. HFFI hopes that increased outreach, combined with more productive preservation incentives, will help achieve the City’s goal to ensure demolitions of historic buildings are the option of last resort.

- Preserve Neighborhood Character—HFFI is pleased to engage in ongoing Planning staff and City Council discussions about Neighborhood Character Preservation, including the current dialog concerning Conservation District zoning. We share the desire to help protect the character of neighborhoods and to ensure housing options in the City.

- Adopt Best Practices for City-Owned Historic Properties, including Renwick Courthouse Complex—HFFI would like to see the Renwick Working Group continue to interact with City staff and meet quarterly to support work to rehabilitate the complex. This model of collaboration among different skill sets from the community looks to be the best chance for success. Beyond the Renwick, the City oversees many historic resources that require sensitive and thoughtful approaches for their maintenance and preservation. HFFI will continue to advocate for best preservation practices to prevent the deterioration and destruction of our historic built environment.

- Assist in Identifying and Protecting FXBG’s cultural historic resources as Master Plans, Small Area Plans, and Comprehensive Planning moves forward—The civic pride distilled from the preservation of historic places and spaces across our community is visible and reiterated in every planning document intended to guide Fredericksburg’s growth and development since the twentieth century. Hiring consultants for assistance in steering future growth, many based outside the Fredericksburg area who lack the depth of awareness that local historians, organizations, and repositories possess about local history, has limited the City’s ability to preserve and nurture our community’s sense of place. Recent planning documents and presentations have shown significant gaps and omissions regarding known archaeological sites and historic resources within the City. Greater awareness of local history and the places that embody it is important to avoid the unnecessary destruction of cultural resources along with any valuable information they could reveal. HFFI wants to work with various city department staff to fill those gaps and support the City’s goal to preserve significant historic resources and protect archaeological sites across the community moving forward.

HFFI’s Board of Directors and staff hopes that the next year will bear witness to the successful completion of longstanding preservation goals in Fredericksburg. To ensure their completion, we would greatly appreciate your help. Show our elected officials and leaders that you care! Write them a note directly (visit City Council’s website to submit comments) or sign HFFI’s petition to show your support!

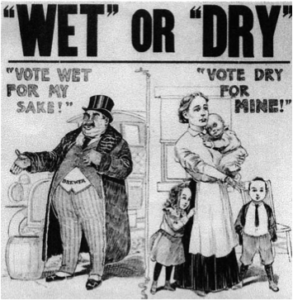

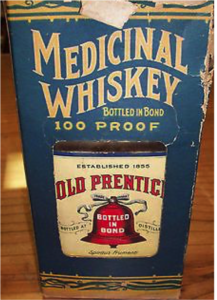

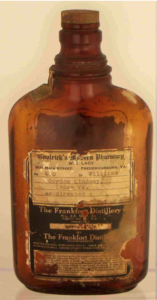

Prohibition came early to Virginia. In 1886, the General Assembly passed the “local option,” which let each county vote to ban alcohol or not. In May 1908, the people of Fredericksburg voted in a referendum to “go dry,” with 53 percent of the vote. Two years later, the “wets” petitioned for another vote, which was signed by 180 citizens, including the town’s biggest saloon owners. The Daily Star proclaimed that “the city is unquestionably better off than ever in its history,” and that “business had in no way been injured by elimination of the saloon.” The 1910 referendum reaffirmed the dry vote by an even bigger margin. However, enforcement of the law proved problematic. In 1911, Fredericksburg convened a special Grand Jury to investigate allegations of Prohibition violations. The jury of prominent citizens trumpeted, perhaps too heartily, that “there is no evidence whatever, much less proof, that there is any violation of the revenue laws.” The panel was, however, very concerned about the crowds that congregated at several corners around town, many located near former saloons.

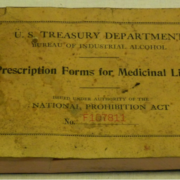

Prohibition came early to Virginia. In 1886, the General Assembly passed the “local option,” which let each county vote to ban alcohol or not. In May 1908, the people of Fredericksburg voted in a referendum to “go dry,” with 53 percent of the vote. Two years later, the “wets” petitioned for another vote, which was signed by 180 citizens, including the town’s biggest saloon owners. The Daily Star proclaimed that “the city is unquestionably better off than ever in its history,” and that “business had in no way been injured by elimination of the saloon.” The 1910 referendum reaffirmed the dry vote by an even bigger margin. However, enforcement of the law proved problematic. In 1911, Fredericksburg convened a special Grand Jury to investigate allegations of Prohibition violations. The jury of prominent citizens trumpeted, perhaps too heartily, that “there is no evidence whatever, much less proof, that there is any violation of the revenue laws.” The panel was, however, very concerned about the crowds that congregated at several corners around town, many located near former saloons. Because bootlegged liquor was hard to get, some Fredericksburgers tried alternatives:

Because bootlegged liquor was hard to get, some Fredericksburgers tried alternatives: Dedicated drinkers had to know where to look to find liquor in Fredericksburg. Like drug dealers today, certain men on certain corners could be relied on to get a bottle. At a nearby country store, people asking for a “pair of size eight shoes” would receive a discreetly wrapped package. Others went straight to the top, such as the reporter who claimed that the best whiskey he drank was served by a local judge.

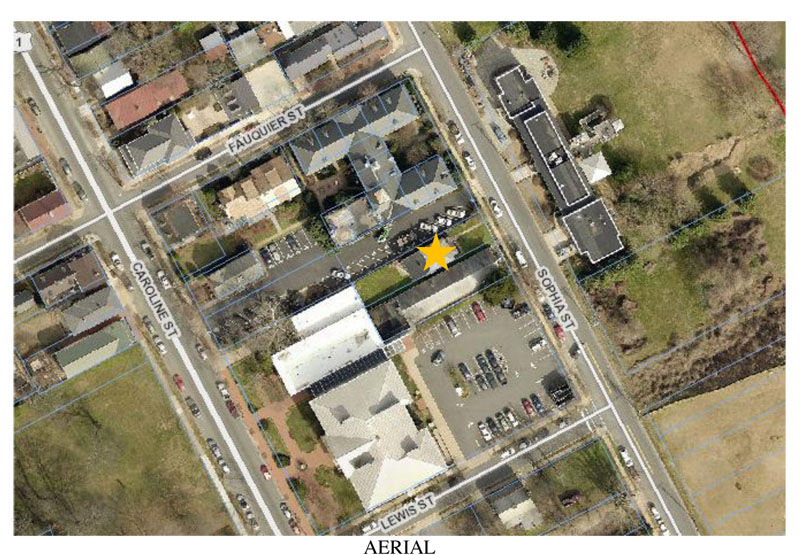

Dedicated drinkers had to know where to look to find liquor in Fredericksburg. Like drug dealers today, certain men on certain corners could be relied on to get a bottle. At a nearby country store, people asking for a “pair of size eight shoes” would receive a discreetly wrapped package. Others went straight to the top, such as the reporter who claimed that the best whiskey he drank was served by a local judge. Although the term “speakeasy” is not used in court records, there were several establishments in town whose patrons were arrested for drunk and disorderly conduct. The Virginia Cafe, the Athens Hotel, and the A-1 Cafe, all located on Caroline Street, were well known for their rowdy customers. The owner of the Fredericksburg Cafe was charged with allowing drinking and gambling and running a “disorderly house,” perhaps the legal term for speakeasy.

Although the term “speakeasy” is not used in court records, there were several establishments in town whose patrons were arrested for drunk and disorderly conduct. The Virginia Cafe, the Athens Hotel, and the A-1 Cafe, all located on Caroline Street, were well known for their rowdy customers. The owner of the Fredericksburg Cafe was charged with allowing drinking and gambling and running a “disorderly house,” perhaps the legal term for speakeasy.