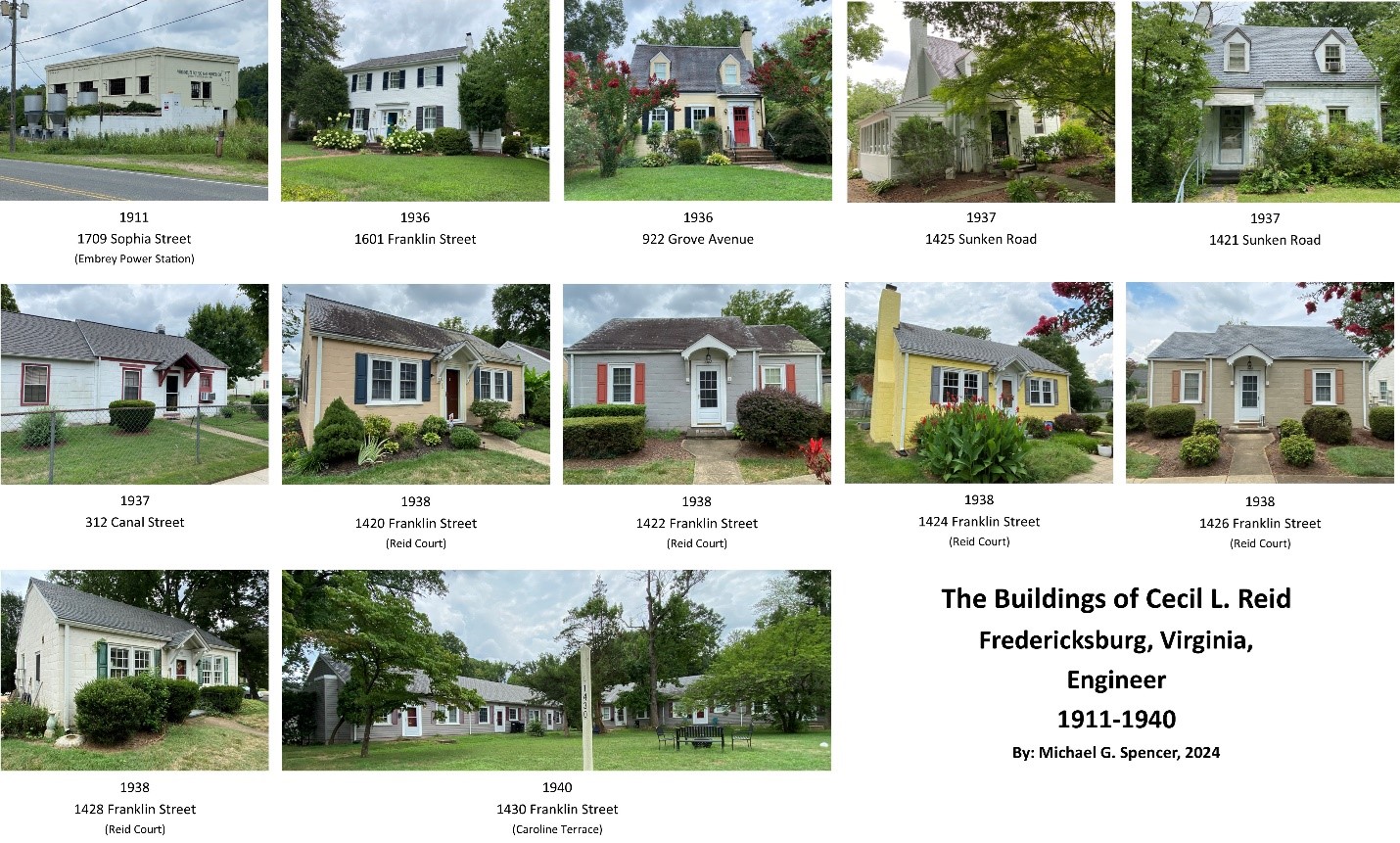

Cecil L. Reid: Engineer of Hydro-Electric Plants, Pragmatic Houses, & City Council

by Professor Michael Spencer, Department of Historic Preservation, University of Mary Washington

Fredericksburg, like many communities in the early to mid-20th century, saw a significant number of concrete houses constructed. Cecil Latta Reid, although not the most prolific builder in the community, was responsible for the design and construction of at least 11 of these, mostly in the College Terrace neighborhood. His pragmatic design approach seemed to appeal to the 1930s mindset, so much so that his 1938 Reid Court development was noted in The Book of Houses, a 1946 publication by John Dean, Regional Economist of the Federal Housing Authority, and Simon Breines, an architect with the New York firm Pomerance & Breine.[i]

However, Reid designed houses only late in his career. His primary work centered on design and construction of hydroelectric plants throughout the South.[ii] The engineering of such early electric works was a job well-suited for Reid, who was noted as “hard driving and relentless” as well as “exact and precise.” A later description saw him as always carrying a slide rule and collapsible steel tape “which he uses at the slightest provocation.”[iii] No doubt Reid’s strong work ethic was, in part, a necessity. Born in 1882 in Rock Hill, South Carolina, Reid lost both his parents, Samuel and Frances, by the time he was 18 years old.[iv] Despite this hardship, he enrolled at Clemson University in 1899 and worked his way through the mechanical engineering program by tutoring, drafting, and working in the dining hall. Even with these jobs, Reid still graduated in 3 years at the age of 20.[v] Clemson would continue to feature prominently in Reid’s life after graduation. He dedicated significant time and resources to the university, including establishing the Baskin Loan Fund in honor of his mother.[vi] Clemson awarded him two honorary degrees, one in 1928 and another in 1953.[vii]

Upon graduation, Reid began working for the Seaboard Air Line Railway where he became acquainted with William C. Whitner of Richmond, Virginia. Whitner by this time was known as a pioneering “waterpower development engineer of the South.” That apparently appealed to Reid, because he began working with Whitner shortly thereafter. The work eventually brought him to Fredericksburg in 1906 where Frank Jay Gould employed him to survey the Rappahannock River and its potential use for hydro-electric power generation. On the basis of Reid’s survey, Gould purchased the old Fredericksburg Power Company and proceeded to finance the construction of a new dam and power plant. Both new structures were designed by Reid, who served as the Resident Engineer under the guidance of his mentor, Whitner.[viii] Work on the dam, later called the Embrey Dam, was completed in August 1909.[ix] In April of the same year, plans for the power plant had been completed and construction began the following year, culminating in 1911 (Figure 1).[x] Although the use of reinforced concrete was a significant departure from traditional Fredericksburg building materials, similar design and construction techniques had been used a few years earlier in the construction of the James River Power Plant located on Belle Isle in Richmond, Virginia.[xi] Reid would go on to design and oversee construction of a number of such power plants, including Virginia Western Power Company’s plant at Balcony Falls in Rockbridge County, Virginia, in 1916.[xii]

When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, Reid enlisted and was appointed Chief Construction Engineer at Camp Bragg (now Fort Liberty) in North Carolina.[xiii] After the war, he continued to design and build hydroelectric plants, although he also dedicated significant time to community service, stating that “every citizen should put public duty above self for it is through this that we can better our community and make the world a bit better for our having existed on it.”[xiv] Reid’s community service included chairing committees to erect two new school buildings in Fredericksburg, creating the Department of Manual Training at Fredericksburg High School (now James Monroe High School), serving as President of the Fredericksburg Building and Loan Association, and eventually serving 9 years on City Council (1933–1942). Despite these accolades, Reid was not driven by the need for power or recognition, expressing in his run for City Council that he was willing to “serve if the citizens wanted him but…if it was a matter of personal preference he would decline the offer.” At the time, Reid was elected to Council with the highest number of votes ever obtained in a contested election—despite never asking for a vote—a testament to his ability and character.[xv]

During his service on City Council, Reid began to design and build a series of homes located in the Kenmore subdivision of the College Terrace neighborhood. Although he was not new to real-estate investing—having bought and sold a number of lots in Fredericksburg—designing and building homes was new ground. Building permits were issued to Reid on the first three houses he designed in 1936—906 (later 918) Grove Avenue, 922 Grove Avenue, and 1601 Franklin Street. The latter, 1601 Franklin Street—ultimately was the most expensive house he would design and build, with a permit value of $4,500—would be a significant departure from his other house designs.[xvi] Designed as a Colonial Revival residence, the two-story central passage building used brick laid in a stretcher bond, whereas Reid’s other houses would employ concrete block, including both 906 and 922 Grove Avenue.

The use of concrete block had advantages over brick at the time, primarily in terms of reduced construction time and cost. With the country still emerging from the Great Depression, cost was a major consideration and would factor into all of his subsequent designs. Concrete was also a material that Reid was quite familiar with, having used it in his hydroelectric plants since the early 1900s. Despite this familiarity, the construction of 922 Grove Avenue, when compared with his later concrete block buildings, suggests that Reid was experimenting to some degree. Rather than laying the concrete block in a stretcher bond pattern, a smaller course of concrete block was inserted every other course, creating an interesting aesthetic. Although this configuration of concrete block appears to be unique to 922 Grove Avenue, slate roofing and cast concrete lintels, with shallow recessed panels, appear in virtually all of his later buildings. Both 906 (918) and 922 Grove Avenue were designed with a Tudor Revival aesthetic, incorporating asymmetrical fenestration and projecting front entries, with 922 Grove Avenue even incorporating a “kick” at the eave. Scroll work was also included in a wood panel above the fixed picture window at 906 Grove Avenue and the door surround at 922 Grove Avenue.

Figure 2: 922 Grove Avenue. Note the cast concrete lintel above the window with recessed panel as well as the scrollwork on the door surround. Close examination of the concrete block walls shows the interesting bond pattern of one course of full-sized block followed by a course of ½ sized block.

Permits were issued for 1421 and 1425 Sunken Road as well as 312 Canal Street the following year. Both Sunken Road houses also incorporated the Tudor Revival aesthetic, with 1425 Sunken Road even using the same door surround as 922 Grove Avenue. However, 312 Canal Street employed a less stylized aesthetic consisting of a symmetrical fenestration with three-bays and a central entry that was covered by a small gable roof supported by brackets on either side. The size of the building was also reduced, resulting in a more cost-effective residence with a permitting value of $1,200, significantly less than Reid’s earlier houses.[xvii]

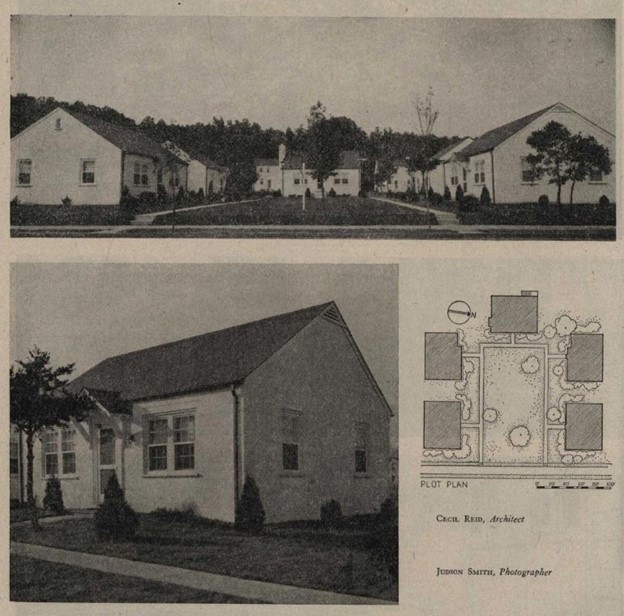

During the summer of the following year, Reid began construction of Reid’s Court, located at 1420–1428 Franklin Street.[xviii] With 312 Canal Street serving as a model, five concrete block houses were erected using three similar plans. Both 1420 and 1428 Franklin Street were perhaps the most similar in design to 312 Canal Street. The only difference was that both 1420 and 1428 incorporated paired windows within the bays flanking the central entry. Located at the end of the U-shaped “cul-du-sac,” 1424 Franklin Street followed a similar design but with an exterior end chimney. The two houses at 1422 and 1426 Franklin Street offered the most variation. Still three-bays wide, the buildings were asymmetrical owing to the west bay of both buildings being recessed. Otherwise, the buildings incorporated many of the same design aesthetics as the other buildings constructed at Reid’s Court. Collectively, the 1938 building permits noted the value of the project at $7,000, approximately $1,400 each, comparable to 312 Canal Street. The individual design aesthetic of these houses was critiqued by John P. Dean and Simon Breines, authors of the 1946 publication, The Book of Houses. With 1426 Franklin Street as an example, the authors compared Reid’s design with mid-century modern aesthetics noting that in:

“…small homes of traditional style such as above [1426 Franklin St.], the windows are little holes knocked in the wall at even intervals. In the modern small house…windows are grouped to admit lots of light at well planned points.”[xix]

However, the authors went on to extol the virtues of the larger five-house development, of which 1426 Franklin Street was a part, noting that individually, the houses were “undistinguished”:

“…by combining them in a pleasing neighborhood plan, the group takes on a character which the individual house does not possess. And a neighborhood of this sort has many advantages in livability which go far beyond the mere pleasant appearance of the structures. With land as plentiful as it is in the United State and with the raw land comprising such a small part of the total cost of a completed house, we may ask ourselves why all our neighborhood developments are not so intelligently planned and constructed as the one shown above.”[xx]

Figure 4: Images from the 1946 publication, The Book of Houses, by John Dean and Simon Brienes. Note the courtyard created by the buildings which are oriented toward the green space and not Franklin Street.

Although novel to Fredericksburg at the time, the idea of a planned courtyard neighborhood, albeit small in scale, echoed aspects of the larger Garden City movement. Begun decades earlier in the early-20th century but popularized in the United States in the 1920s through developments such as Radburn, New Jersey, the movement emphasized affordability as well as interaction with green spaces. Both developments, while vastly different in scale, created neighborhood courtyards that provided residents with community green space free of automobiles, which were relegated to the street or rear of the development.

In 1940, 2 years after completing Reid’s Court, Reid began construction of Caroline Terrace, named after his wife.[xxi] Located at 1430 Franklin Street, adjacent to Reid’s Court, Caroline Terrace consisted of two cinderblock structures each with three units. These units were similar in appearance to Reid’s earlier standalone residences, such as 312 Canal Street, but with some window variations. Like Reid’s Court, Caroline Terrace faced a large communal green space with parking at the rear of the lot accessed via an alleyway. While the houses remained affordable, quality materials, such as slate roofing, were used in construction.

Reid would contract with W.T. Courtney in 1948 to extended his garage on Cornell Street, but the Caroline Terrace development was his last residential project.[xxii] Reid died 7 years later in September 1955.[xxiii] Despite the small number of homes built, his contribution to the College Terrace neighborhood was significant, and he was noted at the time as introducing “some architectural and construction features which have been most pleasing as well as practical.”[xxiv] This contribution is especially noticeable along the 1400 block of Franklin Street, where his homes still help define the area’s character. Also noteworthy are the economical designs he used, which when coupled with the introduction of quality materials and green space, serve as one of Fredericksburg’s few noteworthy references to the interwar (1918–1939) Garden City planning movement.

Endnotes:

[i] Dean, John and Simon Brienes, The Book of Houses (New York: Crown Publishers, 1946), 28–9, 58.

[ii] Free Lance-Star, September 6, 1955, 3:3.

[iii] Free Lance-Star, June 1, 1938, 6:4.

[iv] The National Archives At St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; Record Group Title: Records of the Selective Service System; Record Group Number: 147, accessed August 2024, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/1210104:1002?tid=&pid=&queryid=de623f72-96cb-428d-ac2d-fd51c49bd2e3&_phsrc=MjY1&_phstart=success Source; Free Lance-Star, June 1, 1938, 6:4.

[v] Free Lance-Star, June 1, 1938, 6:4.

[vi] The Newberry Observer, September 6, 1955, 2:5.

[vii] Free Lance-Star, June 13, 1953, 3:5.

[viii] Free Lance-Star, September 6, 1955, 3:3.

[ix] Engineering Record, vol. 61 no. 7, (New York: McGraw Publishing Co, 1910): 197–8.

[x] Electrical Review and Western Electrician, (March 20, 1909): 549; The Free Lance, May 20, 1911, 1:4.

[xi] Street Railway Journal, vol. XXIII no. 1, (New York: McGraw Publishing Co., 1904): 20.

[xii] Rockbridge County News, vol. 32 no. 36, (July 6, 1916): 3:5.

[xiii] Free Lance-Star, September 6, 1955, 3:3.

[xiv] Free Lance-Star, June 1, 1938, 6:4.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Fredericksburg, Virginia Building Permits, 1936.

[xvii] Fredericksburg, Virginia Building Permits, 1937.

[xviii] Fredericksburg, Virginia Building Permits, 1938.

[xix] Dean, John and Simon Brienes, The Book of Houses (New York: Crown Publishers, 1946), 58.

[xx] Dean, John and Simon Brienes, The Book of Houses (New York: Crown Publishers, 1946), 28–9.

[xxi] Fredericksburg, Virginia Building Permits, 1940.

[xxii] Fredericksburg, Virginia Building Permits, 1948.

[xxiii] Free Lance-Star, September 6, 1955, 3:3.

[xiv] Free Lance-Star, June 1, 1938, 6:4.