Historic Bricks and Mortar

by Natalie Chavez and Danae Peckler; edited by Linda Billard

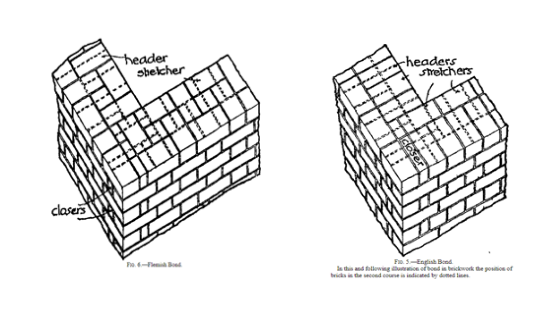

The Lewis Store, HFFI’s headquarters, is the embodiment of honest brick construction in a classic Georgian architectural style from the mid-eighteenth century. This mass masonry brick building has multiple wythes, or vertical sections of brick wall, laid in two different bonds. The Lewis Store’s elevation showcases the stylish Flemish bond, while the interior wall of the building showcases the stronger English bond. Most of the building’s brick dates from its original construction in 1749 and added second story in 1808, although some minor repairs were made to damaged areas during its rehabilitation in 1999 and 2006. Contributing to the Lewis Store’s durability is the craftsmanship and skills of its builders and the make-up of its mortar.

Figure 1: Brick Bonds from Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 4, Part 3, 1911.[1]

All mortars are composed of three main ingredients: a binder or cementing material, an aggregate such as sand, and water. Prior to the late nineteenth century, lime was used as the binding agent. It was created by crushing stone or oyster shells and burning the resulting material to create quick lime that was later mixed with water and sand. Traditional lime mortars are remarkably forgiving of both the weathering of time and the environment, allowing for “some movement in the brickwork without showing signs of cracking under normal seasonal conditions.”[2] This differs greatly from the rigidity of Portland cement, which became commonplace by the early-20th century. Owners of historic brick buildings make a crucial mistake by repairing mortar joints using a Portland-based mortar. While Portland cement has many benefits, its use in historic masonry creates long-term problems, even inducing decay of the bricks themselves.

Figure 2: Image from Colonial Williamsburg Showing Oyster Shells After Burning.[3]

Experts in the field of preservation advocate for using the gentlest techniques in the maintenance of historic brick. Such work is only needed every 100–150 years and, in most cases, a sensitive repointing with lime mortar will last another 100 years unless the repair is addressing the symptom of a larger problem that has gone unaddressed.

You can find more information about taking care of historic brick buildings on HFFI’s website and review Cristine Lynch’s 2012 National Register of Historic Places nomination for the Lewis Store to learn more about our great building!

Other great resources

Traditional brick construction: https://www.buildingconservation.com/articles/traditional-brickwork/traditional-brickwork.htm

Efflorescence https://johnspeweik.com/2011/11/17/efflorescence-of-masonry/

How to identify lime mortar: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fh0Ad3FKDrE

Importance of lime mortar: https://www.ncptt.nps.gov/blog/podcast-episode-33-andy-degruchy-on-the-historic-uses-of-lime-mortar-and-its-continuing-importance-today/

Finding the right

mason for the job: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5TmW8ZvsBUs

[1] The Project Gutenberg EBook of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition,Volume 4, Part 3. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/19699/19699-h/19699-h

[2] Geoff Maybank, “Traditional Brickwork.” https://www.buildingconservation.com/articles/traditional-brickwork/traditional-brickwork.htm

[3] Image from Colonial Williamsburg’s Richard Charlton’s Coffeehouse blog: https://research.history.org/Coffeehouse/Blog/index.cfm/2009/3/4/Lime-Burn

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!