Wet or Dry: A History of Prohibition in Fredericksburg

Wet or Dry: A History of Prohibition in Fredericksburg

By Barbra Anderson

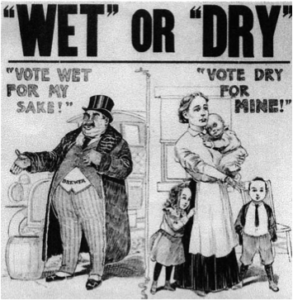

“The saloon is the devil’s headquarters on earth,” declared the Anti-Saloon League in the late 1800s. Alcohol was blamed for every social problem: poverty, domestic violence, crime, ill health, and moral turpitude. The average American man drank 88 bottles of whiskey a year—three times as much as now.

Temperance groups swept the nation. Each member had to take a pledge against “any Spirituous or Malt beverage.” Fredericksburg had three chapters of the Sons of Temperance, which held rallies and parades, weekly meetings, and “grand excursions” to inspire the citizens. Not only did temperance influence the social scene, the “liquor platform” soon dictated state politics.

Prohibition came early to Virginia. In 1886, the General Assembly passed the “local option,” which let each county vote to ban alcohol or not. In May 1908, the people of Fredericksburg voted in a referendum to “go dry,” with 53 percent of the vote. Two years later, the “wets” petitioned for another vote, which was signed by 180 citizens, including the town’s biggest saloon owners. The Daily Star proclaimed that “the city is unquestionably better off than ever in its history,” and that “business had in no way been injured by elimination of the saloon.” The 1910 referendum reaffirmed the dry vote by an even bigger margin. However, enforcement of the law proved problematic. In 1911, Fredericksburg convened a special Grand Jury to investigate allegations of Prohibition violations. The jury of prominent citizens trumpeted, perhaps too heartily, that “there is no evidence whatever, much less proof, that there is any violation of the revenue laws.” The panel was, however, very concerned about the crowds that congregated at several corners around town, many located near former saloons.

Prohibition came early to Virginia. In 1886, the General Assembly passed the “local option,” which let each county vote to ban alcohol or not. In May 1908, the people of Fredericksburg voted in a referendum to “go dry,” with 53 percent of the vote. Two years later, the “wets” petitioned for another vote, which was signed by 180 citizens, including the town’s biggest saloon owners. The Daily Star proclaimed that “the city is unquestionably better off than ever in its history,” and that “business had in no way been injured by elimination of the saloon.” The 1910 referendum reaffirmed the dry vote by an even bigger margin. However, enforcement of the law proved problematic. In 1911, Fredericksburg convened a special Grand Jury to investigate allegations of Prohibition violations. The jury of prominent citizens trumpeted, perhaps too heartily, that “there is no evidence whatever, much less proof, that there is any violation of the revenue laws.” The panel was, however, very concerned about the crowds that congregated at several corners around town, many located near former saloons.

All of Virginia went dry in 1916, and the 18th Amendment enacted national Prohibition in 1920.

By the mid-1920s, Prohibition violations in Fredericksburg became commonplace. Because Route 1 was the only paved road in the area, bootleggers used it to transport “ardent spirits.” Local reporter Warren Farmer described how local police would hide next to the bridges and catch them as they came into town. One rumrunner crashed going around Deadman’s Curve near the National Cemetery. The liquor caught on fire, and he was incinerated beyond recognition.

Because bootleggers often used aliases, the ensuing court cases frequently named the car as the defendant. In 1926, “Virginia vs. Packard Touring Car” involved the transport of 210 gallons of corn whiskey. The penalties were stiff. In another case, two brothers-in-law were convicted for transporting 48 quarts of liquor in their car. Each was fined $50 and given a sentence of 6 months. Moreover, as dictated by law, their car was confiscated and sold.

Because bootlegged liquor was hard to get, some Fredericksburgers tried alternatives:

Because bootlegged liquor was hard to get, some Fredericksburgers tried alternatives:

- “Vine-Glo” was a concentrated grape juice product. Instructions said to dissolve it in water, but warned “Do not place the liquid in a jug away in the cupboard for 20 days, because then it would turn to wine.”

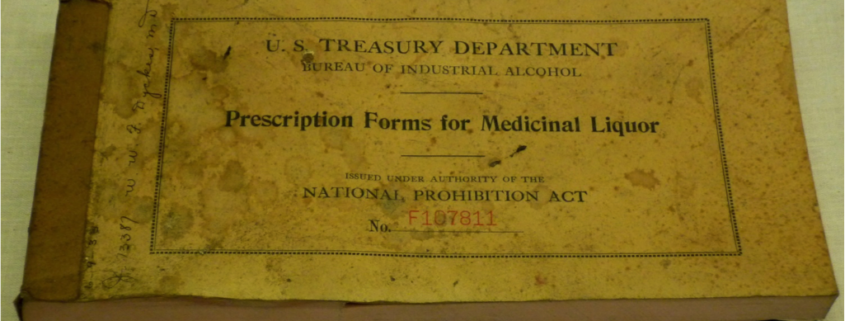

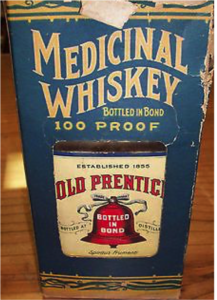

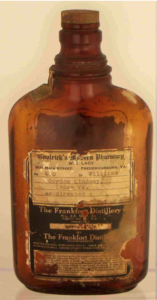

- Doctors could prescribe medicinal liquor for 27 ailments—including cancer, diabetes, and depression—up to one pint every 10 days. Each doctor could write up to 100 liquor prescriptions per month.

- Some tried to make their own liquor, although it could blind, sicken, or even kill a person if not properly processed. Makers of “bathtub gin” converted denatured alcohol to a drinkable form, but the process is prone to both chemical and bacterial mishaps.

According to court and police records, many people were arrested for alcohol offenses. A sampling from the newspapers of the day reveals some colorful characters. “Poodles” Limerick was charged for transporting liquor at the Virginia Cafe. Albert Grimes was fined $20 for being drunk and carrying a concealed weapon (iron knuckles) at the Athens Hotel. Yat Sullivan was convicted of manufacturing and selling liquor. He was fined $250 (about 2 month’s salary) and sentenced to 3 months in jail. “Dinksy” Scott was arrested three times for “unlawfully and feloniously selling ardent spirits.”

Dedicated drinkers had to know where to look to find liquor in Fredericksburg. Like drug dealers today, certain men on certain corners could be relied on to get a bottle. At a nearby country store, people asking for a “pair of size eight shoes” would receive a discreetly wrapped package. Others went straight to the top, such as the reporter who claimed that the best whiskey he drank was served by a local judge.

Dedicated drinkers had to know where to look to find liquor in Fredericksburg. Like drug dealers today, certain men on certain corners could be relied on to get a bottle. At a nearby country store, people asking for a “pair of size eight shoes” would receive a discreetly wrapped package. Others went straight to the top, such as the reporter who claimed that the best whiskey he drank was served by a local judge.

Although the term “speakeasy” is not used in court records, there were several establishments in town whose patrons were arrested for drunk and disorderly conduct. The Virginia Cafe, the Athens Hotel, and the A-1 Cafe, all located on Caroline Street, were well known for their rowdy customers. The owner of the Fredericksburg Cafe was charged with allowing drinking and gambling and running a “disorderly house,” perhaps the legal term for speakeasy.

Although the term “speakeasy” is not used in court records, there were several establishments in town whose patrons were arrested for drunk and disorderly conduct. The Virginia Cafe, the Athens Hotel, and the A-1 Cafe, all located on Caroline Street, were well known for their rowdy customers. The owner of the Fredericksburg Cafe was charged with allowing drinking and gambling and running a “disorderly house,” perhaps the legal term for speakeasy.

Prohibition was repealed in 1933, but selling liquor in Virginia did not become legal until 1934 when the state established the Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control (ABC). In the first month, the ABC granted Fredericksburg 14 licenses to sell beer and wine. The ABC maintained strict control of alcohol throughout the remainder of the century, gradually easing some restrictions. For example, it was not for another 35 years that liquor was sold by the drink. Cocktails were illegal unless you belonged to a “social club” where you would bring your own liquor. On February 9, 1969, the first mixed drink in Fredericksburg—a Tom Collins- was sold at the Princess Anne Inn.

To celebrate the 100th anniversary of Prohibition in Virginia, the Historic Fredericksburg Foundation hosted a Prohibition Pub Tour on Saturday, September 10, 2016.

Much thanks to Nancy Moore and Sue Stone for providing most of the research for this story.

Sources:

Fredericksburg Court Records. Grand Jury, May 1911

Burns, Ken and Lynn Novick, Prohibition (film documentary), 2011

Fredericksburg Police blotters, 1920s

Eaton, Lorraine. Virginian Pilot. “Virginia’s Prohibition History.” Nov 30, 2008

The Free Lance, March 5, 1925

Moore, Nancy. Interview, September, 2016.

Farmer, Warren. Oral History. HFFI, 1998.

Free Lance Star, August 15, 1977

Free Lance Star, May 2, 1934

Free Lance, March 5, 1925

Daily Star, March 10, 1925

Gambino, Megan, Smithsonian Magazine. “During Prohibition, Your Doctor Could Write You a Prescription for Booze.” October 7, 2013.

Clark, Patrick Michael, Rappahannock Magazine. “Drink the Dominion Dry: Prohibition Comes to Virginia”. October, 2015, Volume 2, Issue 1.

Kamieniak, Ted, Fredericksburg: The Eclectic Histories for the Curious Reader. “The Pledge of Brotherhood”.