From Great Virginians to Gloria Swanson: A History of Smithfield and the Fredericksburg Country Club

From Great Virginians to Gloria Swanson: A History of Smithfield and the Fredericksburg Country Club

By Deborah Walters Pederson

(Abridged version—for the full article, see The Journal of Fredericksburg History, Volume 11)

Its tree-lined driveway hints of something from Gone with the Wind. The place has hosted presidents, first ladies, and movie stars. Union generals held council, slaves toiled, and both Union and Confederate wounded received succor there. Royalty, statesmen, Olympic champions, and George Washington visited—the latter running his greyhounds in the fields along the Rappahannock. Music from grand balls floated through its rooms.

Its tree-lined driveway hints of something from Gone with the Wind. The place has hosted presidents, first ladies, and movie stars. Union generals held council, slaves toiled, and both Union and Confederate wounded received succor there. Royalty, statesmen, Olympic champions, and George Washington visited—the latter running his greyhounds in the fields along the Rappahannock. Music from grand balls floated through its rooms.

The property known as Smithfield underwent a transformation common to many of the region’s plantations. In 1753, on the original Crown-issued patent given to Lawrence Smith in 1671, the Brooke family built the first great mansion—Smithfield—by the Rappahannock River. John Pratt, Jr., purchased Smithfield in 1813, but had to rebuild the house on the same location after the great fire in 1819, where it stands today. During the Civil War, Thomas Pratt was the owner of Smithfield—just a stone’s throw away from the Union front line during the December 1862 and May 1863 Battles of Fredericksburg. The Pratt family owned the great mansion until 1905.

The house was the site of a hospital serving the wounded of the Union First Corps’ First Division. Here, General Franklin had his headquarters and watched the 32,000 men of his Grand Division hurl themselves time after time at the lines of Stonewall Jackson, breaking the lines and thrusting through the gaps with victory in their grasp, only to be driven back. In front of the mansion house, General Doubleday moved with his division of infantry, and to the left, General Rufus Dawes made the charge against Jackson’s lines. Nearby, the Union army threw two pontoon bridges across the Rappahannock River to allow the army to cross. Today, within walking distance, are several gun pits in original condition.

A member of the Second Pennsylvania Reserves recounted the seizure of Smithfield on December 12, 1862: “Our regiment was sent to occupy the buildings and out-houses at ‘Smithfield,’ and to hold the bridge across Deep Run actually another, unnamed creek, which had been dammed to create the pond. The main building was Dr. Thomas Pratt’s large brick house, which, being unoccupied, we entered through a window, and found it very handsomely furnished. Colonel McCandless caused the arrest of the overseer and two other white men and sent them off to be detained until the battle as over.”

Smithfield was subsequently converted to a hospital. Another Union infantryman penned this account of his unnerving sojourn near the building later that day: “We came to the halt near a large brick plantation house that was being used for a field hospital. It was an awful sight to see hosts of wounded men being brought there, the ghastly amputating tables, the surgeons at work and the piles of arms and limbs and the poor fellows laid in rows in and around the house and outbuildings. We stopped here but a short time, but all of us were not sorry when we got orders to move.”

From 1866 to 1868, workmen disinterred the remains of 78 Union soldiers at “Pratt’s Farm” (Smithfield), and moved them to the Fredericksburg National Cemetery.

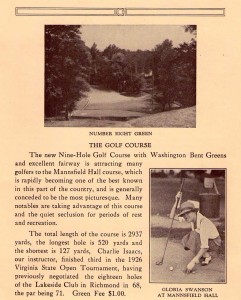

The next owner was Conroy Vance. He bought adjoining property and renamed his home Mannsfield Farm. He was a banker and valued member of the community. In 1922, after he and his wife died in the Knickerbocker Theater in Washington, DC, when the roof collapsed due to heavy snow. Vance’s greatest wish had been for the area to have a country club. His dream came true after his death; in May 1925, several local businessmen got together and formed the Mannsfield Hall Country Club. It was the grandest of openings, with the Sid Shannon Serenaders band, Japanese lanterns glistening, and the townspeople dressed in their best formal clothes dancing till dawn. The Club became a social hub of the community as it is today.

On October, 19, 1928, the nearby battlefields were dedicated on the front steps of Mannsfield Hall Country Club. What a day it was—President Coolidge and many prominent figures came to the Country Club to formally dedicate the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park. More than 5,000 people attended, including many luminaries, as recorded by The Free Lance-Star.

During the ceremony, the United States Marines from Quantico were placed in charge of securing the city streets and escorting the presidential party. Representing the South during the unveiling was Miss Rebecca Mason Lee, great niece of General Fitzhugh Lee and a great granddaughter of Captain Sidney Smith Lee, Robert E. Lee’s brother. Representing the North was Miss Clem, daughter of General Clem, USA (Retired). During the ceremonies, while the President was speaking and the tablet was unveiled, cameras clicked and movie cameras filled the air with the sound of their cranks as thousands of people watched.

Unlike many historic houses in the region, Smithfield/Mannsfield Hall Country Club/Fredericksburg Country Club still lives. The echoes of those who trod the halls and grounds before us still reverberate— the Brookes, the Pratts, their slaves (names unknown, quarters vanished, and burial places unrecorded), soldiers by the thousands, the Vance family, golfers by the foursomes (including Gloria Swanson), and even a president. The story continues, but what a good thing it is to pause and remember, as Judge Francis Brooke mused: “Tis pleasant to recall our former days, what we have been, and done, and seen, and heard, and write it down for those we love, to read.”

Click image to view film footage of the President Calvin Coolidge’s visit to Smithfield and downtown Fredericksburg in 1928.

Sources

Francis H. Brooke, A Family Narrative (New York: The New York times & Arno Press, 1971)

Free Lance-Star, November 23, 1909, January 31, 1922, May 14, 1925, May 13, 1932

Gershon Fishbein, “A Winter’s Tale of Tragedy,” Washington Post, January 22, 2009

Noel G. Harrison, Fredericksburg Civil War Sites, December 1862-April 1865 (Lynchburg, 1990)

Virginia Gazette, November 15, 1770, August 1, 1771, September 2, 1773

Virginia Herald, April 3 and July 10, 1804, May 15, 1819, April 20, 1833, April 22, 1835

For the complete bibliography see the full article in The Journal of Fredericksburg History, Volume 11

Read more about the easement that HFFI holds on the Fredericksburg Country Club in the following Free Lance-Star articles from March, 2016.

March 14, 2016 Free Lance-Star article

March 18, 2016 Free Lance-Star editorial