Preserving FXBG’s Most Affordable Housing

/in Uncategorized /by Danae PecklerWritten by Danae Peckler, HFFI Preservationist

(A shorter version of this article was published in the June 2025 issue of The Front Porch Magazine, page 19)

It is common sense to most people: the lowest priced homes in the market are smaller, older, and not made for HGTV. We’re talking about that tiny apartment, townhouse rental, two-bedroom cottage, converted basement or that place that needs a lot of work. These quirky old places are referred to as “naturally occurring affordable housing” (NOAH) or “market-rate-affordable” by housing advocates, urban planners, and some real-estate industry professionals.

NOAH comprises 75 percent of an estimated 12 million existing affordable units in America today. This categorization refers to the existing stock of privately-owned, unsubsidized, modest-sized houses and apartments that are rented at rates below the regional average. This type of housing is most vulnerable to market pressures like rising property values and redevelopment trends, which can lead to displacement of long-time residents and a decrease in NOAH.

For decades, those advocating for Historic Preservation and/or Affordable Housing have often partnered in the rehabilitation and adaptive reuse of older buildings to create new housing opportunities–a collaboration supported by both state and federal tax incentives geared towards the reuse of historic buildings and increase in low-income housing opportunities. Similar examples of this type of adaptive reuse work in the City of Fredericksburg includes the conversion of the old G&H factory and Maury School into condominiums and some office space in the 1990s and 2000s. More recent examples include the adaptive re-use of the Janney-Marshall Warehouse on lower Princess Anne Street into apartment units.

The Preservation Compact, a non-profit Community Impact Corporation and policy collaboration thinktank, and the Institute for Housing Studies at DePaul University, have studied NOAH extensively across the country to support its preservation. “Unsubsidized, naturally occurring affordable housing (NOAH) comprises the majority of affordable rental housing, and needs investment. The responsible small businesses that own NOAH need support.” This collaborative effort identified effective NOAH preservation strategies based on market conditions.

In lower cost markets, the vast majority of NOAH is owned by competent, responsible private market owners. In these neighborhoods it is likely that small and mid-sized for-profit owners can efficiently preserve affordability, but they are typically not looped in to government and industry policy discussions, and may need support.

In markets where values are rising, NOAH is lost over time as prices and rents increase. Mission driven developers play a critical role in these neighborhoods to keep NOAH affordable over the long term. Those developers need tools and effective strategies in strengthening markets…

Increasingly stressed by rising market values, Fredericksburg’s NOAH seems to be in a period of significant transition. So what do we know about this important sector of our housing stock? Last month, City Planning Commission and staff discussed “tracking housing production” with City Councilors without mention of any plan to monitor our existing housing stock or identify what NOAH the city may have lost in recent years (see points made at joint meeting of City Council & Planning Commission on Comp Plan revisions: 2025.4.9_PC_CompPlan_comments-from-PC-CC-joint-mtg).

How do we know if FXBG is growing or losing its most affordable housing? Who are the competent and responsible private owners and mission-driven developers that steward our NOAH? Do you know any of these kind of developers? Are they included or involved in local affordable housing groups? What can we do to further support the preservation of our City’s older and smaller homes?

A circa-1930s triplex on Maury Street. This kind of NOAH might benefit greatly from an increase in the City’s Rehabilitation Tax “Credit” (or relief) program, designed to support safely updating and improving older buildings in town. State law provides quite a bit of room for the program’s expansion.

HFFI is proud to know one such competent and responsible private owner – the president of our organization, David James. James has been one of the City’s competent, responsible, small-scale landlords for more than 20 years, maintaining nine affordable units that rent from $600 to $1,050 a month. A self-taught handyman, David does the basic maintenance and repair work for his properties. He hasn’t raised the rent for more than a decade, and he knows his tenants fairly well. Recalling their names and occupations with ease: a plumber, retired railroad engineer, safety contractor, bartender, pizza chef, convenience store clerk, nurse, civilian in food service at Quantico, and bookmobile driver.

“The greatest threat to affordable housing is not the lack of resources to build, but the lack of resources to operate, maintain, and repair,” says Priya Jayachandran of the National Housing Trust in her op-ed, “In the Rush to Build, Existing Affordable Housing Is Falling Apart,” online at Shelterforce.org.

The benefits of preserving affordable housing are clear and compelling. First and foremost, only by preserving existing housing at the same time as we build new housing will we move the needle on our supply shortage; building new units while hemorrhaging existing stock is treading water at best and losing ground at worst.

Preserving housing is much less expensive than building new…. Preservation leverages prior investments in affordability by extending the life of homes we’ve already created. It’s also faster—an affordable home that is renovated and preserved can be available to families in need of housing in a fraction of the time it takes to build new housing.

Preservation uses less energy and carbon than building new. And most importantly, preserving existing housing averts displacement of residents and addresses housing stability as well as supply.

Prior to its June 2025 demolition, this 1890s dwelling on Liberty Street sold in November 2022 for $100k less than what the owner is hoping to get from the vacant lot now that the property is back on the market in July 2025. A slew of unresolved maintenance code violations were able to go unaddressed in recent years.

Want to learn more about FXBG’s efforts to Preserve NOAH and safely rehabilitate our existing building stock?

HFFI Op-Ed: Most Affordable Housing Isn’t New

2025-2029 City of Fredericksburg’s Community Block Development Grant Action Plan

- “Fredericksburg has limited issues with substandard housing. 2016-2020 CHAS

data reveals that 105 low to moderate-income renters reside in housing lacking complete plumbing and

kitchen facilities. This indicates there is some need for quality rental housing and rental property

maintenance” (p. 24). - “A declining level of homeownership in Fredericksburg has been a concerning housing trend for several

decades. Homeownership levels during preceding decades were 37.3 percent in 1970, 40.9 percent in

1980, 50.9 percent in 1990, 36 percent in 2000, and 38 percent in 2010. The 2020 ACS identifies a 39

percent homeownership rate” (p. 50). - “According to the 2018 City-wide market analysis, there are approximately 12,000 housing structures in

Fredericksburg. This inventory includes a mix of 45% multifamily units, 40% single-family detached

homes, and 15% townhomes/attached units” (p. 50). - “Exterior condition surveys of City neighborhoods have identified several general areas with a

concentration of housing units in need of repair. Conditions requiring attention are defined as those that

are detrimental to the household’s health and safety, including but not limited to leaking roofs,

inadequate electrical service, and inadequate or failing plumbing. The real estate market has often

resulted in the renovation of many substandard units, but there are still pockets of substandard

dwellings throughout Fredericksburg” (p. 60). - “The age and condition of the local housing stock have also been a factor in developing CDBG programs.

27% of Fredericksburg’s housing units were built before 1950. While many of these units are historic

dwellings that contribute significantly to the overall charm and attractiveness of the City, the

maintenance requirements of older homes can be substantial. In instances where the occupants are

unable to perform the appropriate maintenance, housing conditions can deteriorate to substandard

levels very quickly and threaten the health and safety of the occupants. In addition, substandard housing

units that must be abandoned represent losses from the local affordable housing stock” (p. 62). - “Affordable housing is a basic component for maintaining a vibrant and diverse community of

neighborhoods. The City of Fredericksburg already has the majority of the region’s subsidized and

assisted housing, as well as the majority of the area’s available rental housing. The City seeks to maintain

this existing level of housing while concurrently working to conserve its other residential neighborhoods.

There is a strong need, for instance, to enhance the community’s demographic stability by concentrating

on homeownership opportunities” (p. 133).

Developing an Anti-Displacement Strategy from Local Housing Soultions.org

Ways to Combat Displacement and Lack of Affordable Housing [and Preserve NOAH] from Center for American Progress

VA250 Preservation: The Lewis Store Restoration Project

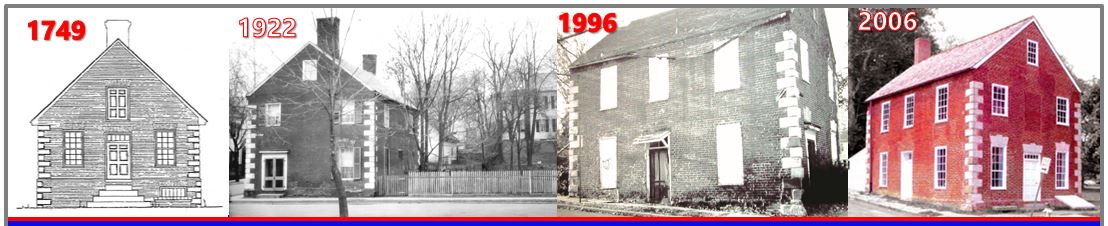

/in Uncategorized /by Danae PecklerOne of the oldest commercial store buildings in America, Historic Fredericksburg Foundation, Inc. (HFFI) restored this rare surviving example of American commercial retail architecture with the help and support of our community between 1997 and 2007. And we’re doing it again in 2025-2026!

A generous grant from the state’s VA250 Preservation Fund is offsetting the cost of repairing the store’s exterior envelope. Our restoration work includes repointing deteriorated brickwork, preserving its iconic sandstone quoins, and replacing the wood-shingle roof that is at the end of its functional life—all in accordance with national standards, set by the Secretary of the Interior (SOI), and preformed by experienced historic tradespeople in our region.

A generous grant from the state’s VA250 Preservation Fund is offsetting the cost of repairing the store’s exterior envelope. Our restoration work includes repointing deteriorated brickwork, preserving its iconic sandstone quoins, and replacing the wood-shingle roof that is at the end of its functional life—all in accordance with national standards, set by the Secretary of the Interior (SOI), and preformed by experienced historic tradespeople in our region.

HFFI is thrilled to celebrate the 250th anniversary of America’s Revolutionary War and Fredericksburg residents’ contributions to the cause for independence. Lewis lived in a house built in 1746 and designed to face the river on the ridge just behind the store with his wife, Catherine Washington (a cousin of his second wife, Betty Washington, George’s younger sister). A dendrochronology study of Lewis’ store confirmed its construction in 1749, just a few years later.

Conjectural drawing by Joseph Dye Lahendro, Architect PC, of the circa-1749 Lewis Store east elevation.

Originally one-and-a-half stories tall, the brick store was designed to house, market, and sell merchandise transported to Fredericksburg by the Lewis family’s shipping business. Its unique, durable, and stylish Georgian architecture was also an advertisement—reflecting the wealth and commercial aspirations of one of Virginia’s richest families. Customers could purchase refined goods like salt, brown sugar, molasses, coffee, tea, white and brown linens, stockings, handkerchiefs, tobacco, rum, spices and medicines, and writing paper at this store.

America’s “consumer revolution” helped to fuel the colonists’ rebellion as the British government increasingly levied taxes on all sorts of popular commodities. Colonial merchants like Fielding Lewis (1725-1781) and his second wife, Betty Washington, became some of the war’s biggest proponents. The Lewis family invested heavily–emotionally, socially, and financially–in the revolution. Fielding Lewis’ business, ships, and trade network were used to purchase and deliver goods and ammunition to Colonial troops.

Want to lend a hand to help us Restore the Store!? Support HFFI’s commitment to match 50% of the cost of this important restoration with a cash donation – click here!

Powered by volunteers, generous donations, and a shared dedication to stewarding the historic fabric of Fredericksburg for more than 70 years, HFFI has worked to preserve the history we can see and feel. Thank you, fellow fans of historic Fredericksburg, for continuing to support our efforts to keep Fredericksburg’s history alive!

HFFI’s 2025 Preservation Advocacy Report

/in Uncategorized /by Danae PecklerAt the last regular meeting of Fredericksburg City Council, HFFI presented a summary of important Historic Preservation goals and called upon the City’s leaders to make progress on the “big 3” most impactful and achievable initiatives. These goals and priority tasks were created by professionally trained City staff, based on residents’ input and insights from professionals working in Preservation locally. You can read more in HFFI’s 2025 Preservation Advocacy Report to Local Leaders

HFFI members and anyone who signed our “big 3” petition in the last year may recall these top-priority goals:

- Study it! Conduct a city-wide Historic Preservation Economic Impact Study to quantify the ways in which preserving our City’s historic fabric supports the local economy, good jobs, the health of our environment, our sense of place, and maintains existing affordable housing and higher density development than areas outside the downtown core. This kind of study has been a local Preservation goal since 2010 and emerged from the Preservation Plan (Chapter 8) adopted by Council in 2021. It was again recommended by an expert hired consultant in 2023. A study of Preservation’s economic impact across the entire City costs the same as recent economic feasibility studies funded by the City for just two individual properties.

- Support it! The goals set by City staff with and based on residents’ input are important and could be achieved with greater support. Ensuring the preservation of our City’s most unique, irreplaceable, and valuable cultural assets should not be a job limited to a few staff members. Create the Historic Preservation Advisory Committee as presented by staff on September 12, 2023, to increase awareness and provide greater support for City staff’s efforts.

- Expand it! The City’s Rehabilitation Tax Exemption program is largely unknown and rarely used. State law allows for a significant expansion of its scope to aid in the preservation and adaptive re-use of the existing built environment, This program could be tweaked for greater effect and efficiency to assist in safely upgraded and rehabilitating our aging, if not officially “historic,” building stock. The expansion of this program was one of the biggest takeaways from a 2023 City-commissioned expert report and was also listed as a top priority task of the Clean & Green Commission’s Sustainability Committee in 2021. Check out the City’s 2023 report: Historic Preservation Recommendations: Economic Incentives and Spot Blight/Demolition by Neglect

Want to learn more about the many ways in which the City’s Historic Preservation goals overlap with other important initiatives and advocate for HP in FXBG? Reach out to HFFI at preservatinoist@hffi.org

Architect Philip Stern’s Life and Architectural Legacy in Fredericksburg

/in Uncategorized /by Danae Pecklerby Inga Gudmundsson McGuire

A shorter version of this article was published in the April 2025 issue of Front Porch Magazine.

In and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, architect Philip Nathaniel Stern’s legacy sits in plain sight. On streets like Caroline (previously Main), Washington Avenue, and William (Commerce), his oeuvre includes numerous public buildings that anchor downtown Fredericksburg occupying corner lots and coveted plots of land. From his office in the Law Building (910 Princess Anne Street) from 1909 to 1949 (at least), Stern supplied Fredericksburg, neighboring counties, Winchester, Richmond, and far-flung states such as Mississippi and New York, with his architectural expertise and knowledge. Many of his completed designs, both commercial and residential, are extant to this day. While extensive research continues on the life and work of Philip Nathaniel Stern (1878–1960), an overview of his architectural career in Fredericksburg, which spanned four decades, is laid out below in hopes that more interest and discovery into Stern will be sought out in the future.

Philip Nathaniel Stern was born, along with his twin sister Katharine Wyman Grumell (nee Stern), on April 15, 1878, in Bangor, Maine. His parents, Jacob Stern (1844–1913), a German-born merchant married Maine native, Eunice Wyman Walker (1848–1924), in December 1876.[1] The Sterns operated a store aptly named Stern & Co. from 1871 until 1887, which featured fine goods.[2] A mainstay in Bangor, Stern & Co. remained opened until 1887 when it appears Jacob Stern fell into debt and declared bankruptcy, prompting Jacob and Eunice to move their young family to Karlsruhe, Germany, Jacob Stern’s hometown.[3]

Archival resources in the United States offer scant information about Philip Stern’s childhood in Germany or his eventual return to this country. At the age of eighteen, Philip Stern enrolled in the architecture program at the Royal Technical University of Karlsruhe, now the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, in the winter of 1896 where he studied for the next three years.[4] The first documentation that Stern was back in the United States following the family’s trans-Atlantic move came in June 1901.[5] Two years after leaving school, Stern, now a 23-year-old young man, was working as a draughtsman in Chicago, Illinois, for the well-known D. H. Burnham Co. architectural firm.[6] Stern’s stint in Chicago, however brief, came at an exciting time in the city’s history, following the city’s post-1871 fire which sparked rebuilding and growth. The young draughtsman would have been surrounded by new technological advances, materials, and thought, dictating the changing architectural styles of Chicago in the latter half of the nineteenth century from Richardsonian Romanesque to Beaux Arts. Stern’s introduction and immersion into the Chicago School along with his architectural degree provided a strong foundation for his future career in Fredericksburg.[7]

In the early years of the twentieth century, the fledgling architect led a transient life, traveling between Germany and the United States somewhat frequently. In August 1901, Stern, along with his sister, left New York for Germany on the steamship Vaderland. Almost three years later in May 1904, Stern returned alone to the United States on the Rotterdam, settling in Baltimore, Maryland. Three months prior, in February 1904, a fire destroyed over seventy blocks of buildings in downtown Baltimore, presenting an opportunity for young architects like Stern to help rebuild the city.[8] While working in Baltimore, Stern visited Fredericksburg, Virginia at least twice, in April and December of 1905.[9] That December, he stayed with the prominent Shepherd family, whose patriarch, George W. Shepherd Sr. (1830–1909) was the “leading dry goods merchant” at that time.[10] Soon after his first visit, the “rising young architect of Baltimore” would become inextricably tied to the family and town when, in December 1906, he married one of three Shepherd daughters, the “well known and loved” Mary “Mamie” Glassel Shepherd (1875–1960).[11] Soon after their marriage in Fredericksburg, the newlyweds returned to Baltimore, where Stern continued to work, although research did not uncover any buildings in Baltimore attributed to him.[12]

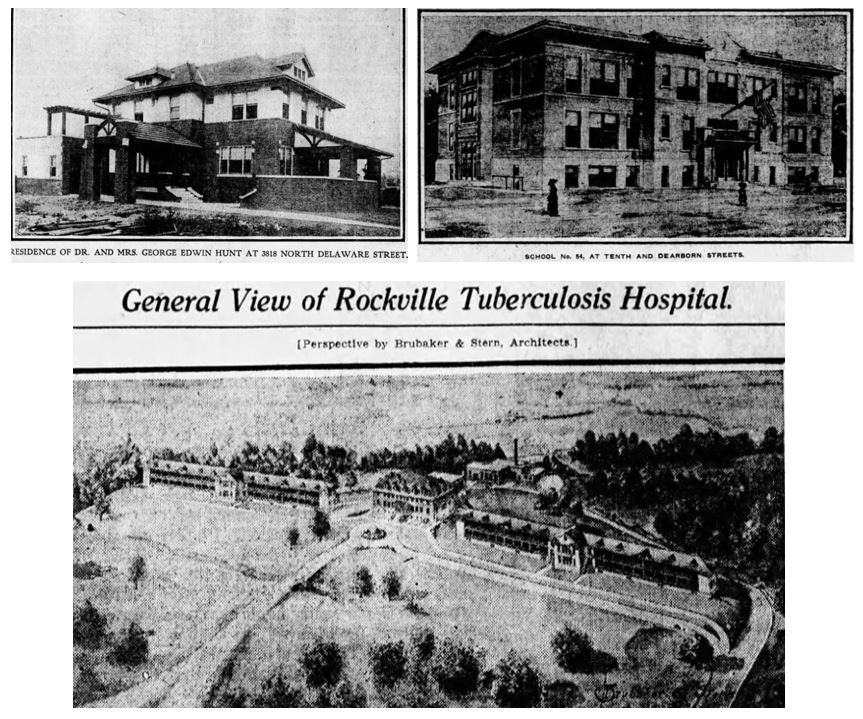

In Baltimore, Stern received a “very lucrative position” to join the architectural firm of Henry C. Brubaker Jr. (1874–1942), in Indianapolis, Indiana.[13] Moving in June of 1907, the Sterns would remain in Indianapolis for two years, Stern quickly becoming an important asset to Brubaker’s firm. In 1908, the two architects formed Brubaker & Stern, successfully winning a variety of large contracts for numerous Indianapolis area projects including the No. 54 School Building (1909), a residence for prominent Indianapolis dentist George Edwin Hunt (1909), and most notably the Rockville State Tuberculosis Sanitorium (1909).[14]

In 1910, Brubaker and Stern added a third architect to their firm, Harry E. Boyle (1881-1947), who operated their Evansville, Indiana office, creating Brubaker, Stern, and Boyle.[15] The firm continued until 1913, when the architects disbanded.[16] By then, Boyle had laid a strong foundation and client base in Evansville and Brubaker had begun to focus his architectural endeavors in Mexico and Texas.[17] As for Stern, once again he would be pulled back to Fredericksburg, this time for good.

While living in Indianapolis, Stern is attributed with designing his first building in Fredericksburg, the former Lafayette School (1908), presently the Central Rappahannock Regional Library on Caroline Street. This anomaly, the only work completed prior to Stern moving to Fredericksburg in 1909, seems somewhat estranged from Stern’s future work in town. The building, which blends both Classical Revival and Romanesque Revival features, is what architectural historian Richard Guy Wilson noted as “more typical of the nineteenth century than of the twentieth” indicating “a lingering Victorian sensibility.”[18] The building’s compound arches, prominent belt course, and corbel detailing above the main entrance do speak to the Romanesque style features that reached the height of their popularity in the decades prior, while the pilasters, pedimented double-hung windows, and central fanlight, seem more aligned with the Classical Revival or Beaux Arts architectural styles, both favored at the turn of the century.

In fall of 1909, Mary and Philip Stern returned to Fredericksburg from Indianapolis following the death of Mary’s father, George W. Shepherd Sr.[19] Whether Stern remained an active partner in business firm with Brubaker and Boyle after this move is unclear, but the architect did embark on his own endeavors in Virginia right away, building a successful architectural business and becoming a well-known architect at both the local and state levels. Stern brought skill and a capable knowledge of architectural design to the growing city of Fredericksburg. Along with his experience working in large metropolitan cities such as Chicago, Baltimore, and Indianapolis, his connections to the prominent Shepherd family and successful completion of the Lafayette Elementary School building created a foundation for Stern’s architectural career in Fredericksburg and surrounding area that only seemed to solidify with time.

In late November 1909, Stern, in collaboration with architects Charles M. Robinson (1867–1932) and Charles K. Bryant (1869–1933), completed plans for the first two buildings of the proposed Fredericksburg State Normal School.[20] Although Robinson is credited with the Jeffersonian Classical Revival style designs for both Monroe Hall (1909–1911) and Willard Hall (1909–1911), Stern superintended the construction of both buildings.[21]

Stern’s institutional, commercial, and residential designs constitute a fair portion of the city’s early-twentieth century landmarks, easily pointed out when driving or walking through downtown Fredericksburg. The architect seemingly pulling from the architectural elements of the colonial and classically adorned buildings around him, applying fanlights, broken pediments, symmetrical facades, dormers and columns to his own original designs at the Princess Anne Building (1910), Commercial State Bank (1911, Crown Jewelers), and the nearby Stafford County Courthouse (1922), as well as the houses at 1304 Washington Avenue (1910), 1111 Prince Edward Street (1914/1923), 407 Fauquier Street (1926), nearby Little Falls on Kings Highway (1915), 804 Prince Edward Street (1923), and 507 Lewis Street (1929).[22]

The Commercial State Bank at the southwest corner of William and Caroline Streets was completed erected in 1910. It has been heavily altered since this ca. 1925 photograph was taken.

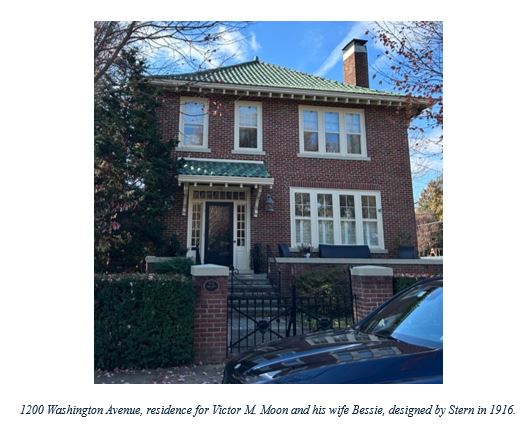

Stern’s residences exhibited other architectural styles popular during the early-twentieth century, some with eclectic elements from the Stick, Craftsman, and Prairie styles. These works include the house at 1307 Washington Avenue (1911), two sister residences at 1308 and 1310 Caroline (1911), 1200 Washington Avenue (1916), and two bungalows built in Stafford County (1910 and 1916, locations for both unknown).[23] Stern’s Lee-Maury School building (1911, demolished) in nearby Bowling Green has Stick-style features like decorative tussles in the gables, wide overhanging eaves, and general applied ornamentation.[24] These buildings, in contrast to the bulk of Stern’s Classical and Colonial Revival designs, showcase the architect’s flexibility and proficiency in providing each client, whether a local businessman or a board of trustees, their desired style and type of building.

His architectural career included a variety of educational and industrial buildings. Along with his early involvement at what is now the University of Mary Washington, the former Lafayette Elementary School, and the Lee-Maury School in Bowling Green, Stern is attributed with designing various other schools in the area, his most impressive school design being the Fredericksburg High School Building, now known as Maury (1919).[25] Some of Stern’s original designs for commercial and industrial establishments are no longer extant, like Sunshine Laundry (1929), Virginia Excelsior Company Office Building (409 Caroline, 1910), the Liberty Cafe Lunchroom and Store (500 Caroline, 1918), and Mullen and Mullen Office (707 Princess Anne, 1922).[26]

He also provided plans for improvements, additions, and interior alterations to existing buildings on streets like William, Caroline, and Princess Anne. Stern directed the interior renovation of the Mansfield Country Club (Fredericksburg Country Club) in 1925, supervised the construction of the Planters Bank Building (1927, now Ava Laurenne Bride), expanded “The Busy Corner” store at 321 William in 1925, and remodeled the Commercial Cafe in the long-demolished Bradford Building (1935).[27] An important legacy of Stern’s is also the numerous alterations he designed for the old Mary Washington Hospital on Sophia Street including additions in 1910, 1915, 1927, and 1933.[28] Stern worked on the interiors of numerous historic houses and landmarks in and around Fredericksburg. Names like Kenmore, Rising Sun Tavern, Mary Washington Home, John Paul Jones House, Sabine Hall in Warsaw, Snowden, Rokeby in King George, Hayfield in Caroline County, and the Knox House (Kenmore Inn) were restored, or rather renovated, by Stern beginning in 1911 when he first worked on Hayfield to his last known restoration work on the Rising Sun Tavern in 1938.[31]

He also provided plans for improvements, additions, and interior alterations to existing buildings on streets like William, Caroline, and Princess Anne. Stern directed the interior renovation of the Mansfield Country Club (Fredericksburg Country Club) in 1925, supervised the construction of the Planters Bank Building (1927, now Ava Laurenne Bride), expanded “The Busy Corner” store at 321 William in 1925, and remodeled the Commercial Cafe in the long-demolished Bradford Building (1935).[27] An important legacy of Stern’s is also the numerous alterations he designed for the old Mary Washington Hospital on Sophia Street including additions in 1910, 1915, 1927, and 1933.[28] Stern worked on the interiors of numerous historic houses and landmarks in and around Fredericksburg. Names like Kenmore, Rising Sun Tavern, Mary Washington Home, John Paul Jones House, Sabine Hall in Warsaw, Snowden, Rokeby in King George, Hayfield in Caroline County, and the Knox House (Kenmore Inn) were restored, or rather renovated, by Stern beginning in 1911 when he first worked on Hayfield to his last known restoration work on the Rising Sun Tavern in 1938.[31]

Stern newly designed a few churches in Virginia, all of which lie outside of the city’s boundaries. St. Paul’s Episcopal Church (1914) in Warsaw; New Hope Church (1915) in Stafford County; and St. Anthony Catholic Church (1916) in King George County are all attributed to Stern. Interestingly, his church designs vary in material and layout.[29] In 1919, Stern also renovated the historic St. John’s Episcopal Church in Warsaw, and in 1925 completed an interior renovation of Fredericksburg’s St. George’s Episcopal Church.[30]

On June 30, 1960, Philip Stern died at the Riverside Convalescent Home, formerly the Mary Washington Hospital on Sophia Street, the same building he had worked on and improved his whole architectural career in Fredericksburg. Philip and Mamie Stern never had children. At the time of their deaths, just a few months apart, their estate was estimated at a staggering $225,000 dollars in 1960, close to $2.3 million dollars in 2025.

This article, neither comprehensive nor extensive, was written in hopes that it would generate more interest and research into architect Philip Stern. His career and legacy, while solidified in Fredericksburg, extends farther into the state and beyond. His restoration work, original architectural designs, involvement in the American Institute of Architects (one of four founders of its Virginia chapter in 1914), Kiwanis Club, and numerous other local and state level committees provides a lens into the architectural profession during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century as well as the development of Fredericksburg and the surrounding area from 1910 to 1960.[32] Only the start of my research into Philip Stern, this article acts as the kickstart into uncovering the architect’s legacy and better understanding his impact on the Fredericksburg area.

Citations:

[1] Bangor Maine Town and Vital Records 1819-1891, 534, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99FP-N4H6?i=533.

[2] “Jacob Stern,” Bangor Daily Commercial, September 30, 1887.

[3] “Bangor and Vicinity,” Bangor Daily Commercial, October 10, 1887″; Jacob Stern Dead”, Bangor Daily Commercial, December 1, 1913; “Philip N. Stern Dead; Retired Architect, 82,” The Free Lance-Star, June 30, 1960; Jacob Stern, Find A Grave, accessed November 10, 2024 https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/253000536/jacob-stern#view-photo=271540071.

[4] Wells, John E., The Virginia Architects, 1835-1955: A Biographical Dictionary, 1997, 430. https://archive.org/details/bwb_T2-ERT-433/page/430/mode/2up?q=stern.;

Matrikel der Gr. Polytechnischen Schule Carlsruhe und der Technischen Hochschule, accessed November 10, 2024, https://digital.blb-karlsruhe.de/blbihd/content/pageview/6635276, 83. Note that Stern’s AIA folder says that he graduated from the program in 1904, which does not match the university’s records found. Matrikel der Gr. Polytechnischen Schule Carlsruhe und der Technischen Hochschule, accessed November 10, 2024, https://digital.blb-karlsruhe.de/blbihd/content/pageview/6635653, 14.

[5] Stern’s parents continued to live in Karlsruhe until Jacob’s death in 1913. Karlsruhe Death Register, Certificate No. 1696, 1913, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/57557:61003?_phcmd=u(%27https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/search/collections/61003/?name=jakob_stern&successSource=Search&queryId=eba5ad5a-2822-43a0-b84a-aabed08be299%27,%27successSource%27). “Welcome to the City of Rockland,” The Bangor City News, June 20, 1901, 2.

[6] 1901 Passport Application, accessed November 10, 2024, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/1096188:1174?tid=&pid=&queryid=3f8117ed-2c80-4196-8ff8-e6bcc895b2fd&_phsrc=Bfa1611&_phstart=successSource; “Philip N. Stern,” The Daily Star, May 5, 1922. Note, that in his passport application, he uses the address of B. B. Thatcher, a prominent Bangor resident who married two of Eunice Stern’s sisters. “Hon. B. B. Thatcher,” Bangor Daily Commercial, June 2, 1906.

[7] Lowe, David Garrad, “Architecture: The First Chicago School”, Encyclopedia of Chicago, accessed December 10, 2024, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/62.html.

[8] Badertscher, Eric, Let’s Take a Look at Maryland, https://research.ebsco.com/c/n4ikcb/viewer/html/65tul2zmdb.

[9] “Newsy Nuggets,” The Daily Star,” April 17, 1905, 3.

[10] “Current Comments,” The Free Lance-Star, December 28, 1905; “Laid to Rest,” The Free Lance-Star, October 7, 1909. Shepherd Jr. served as best man in the Stern-Shepherd wedding, which could be evidence of a close friendship between the two and possible connection to the Shepherd family and Fredericksburg initially. “Shepherd-Stern,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, December 13, 1906.

[11] While researching, the only connection to Fredericksburg, Virginia prior to Stern’s visit in 1905, was a mysterious note in the Bangor Commercial newspaper in 1887. It noted a man, who was thought to be Jacob Stern, had committed suicide in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Called a “sensational report,” to boost newspaper sales, perhaps the Sterns had connections to Fredericksburg that led to this false report.; “Stern-Shepherd,” The Free Lance-Star, December 15, 1906. At the time of their wedding, Mary was thirty-one years old, and Stern was twenty-eight.

[12] “Newsy Nuggets,” The Daily Star, June 17, 1907, 3. Research did not reveal any buildings in Baltimore that Stern designed, or if he was working for an established firm or as an individual architect.

[13] “New Member of Architect Company,” The Indianapolis News,” June 29, 1907, 12.

[14] “Architects Chosen,” The Indianapolis Star, March 27, 1909, 7; “Finish New School Plan,” The Indianapolis Star, August 24, 1909, 14; “How Others Have Built,” The Indianapolis Star, August 22, 1909, 44; ” The P.G.C. and G.E. Hunt Society, Circa 1915,” accessed November 10, 2024, https://images.indianahistory.org/digital/collection/dc013/id/293/.

[15] Marchland, Joan C., Sunset Park Pavilion Nomination, National Register of Historic Places, accessed January 31, 2025, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/132005003.

[16] “Harry E. Boyle & Company Incorporated Architects & Engineers are successors to Brubaker, Stern, and & Boyle,” Evansville Courier and Press, October 26, 1913, 28. It seems that 1913 marks the year Boyle left the firm. Brubaker and Stern continued to work together in some capacity, with a contract awarded to the pair in 1919. “Three Homes Are Started,” The Indianapolis News, July 23, 1919.

[17] “Heads New Architectural Firm,” The Evansville Journal, October 12, 1913, 17; “Gets Mexican Contracts,” The Indianapolis News, February 19, 1910, 2.

[18] Richard Guy Wilson, et. al. “Central Rappahannock Regional Library,” Society of Architectural Historians, SAH Archipedia, accessed January 29, 2025, https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/VA-01-FR32.

[19] “Current Comments,” The Free Lance-Star, October 7, 1909, 3.

[20] “Building Plans Are Approved,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 13, 1909, 2.

[21] “Building Plans Are Approved.”

[22] “Hotel Directors,” The Free Lance-Star, May 31, 1913; “New Residence,” The Daily Star, October 12, 1914; “Commercial State Bank” The Daily Star, May 18, 1912; “Building New Residence,” The Daily Star, July 8, 1925; “New Court House,” The Daily Star, May 9, 1922; “To Build Brick Residence,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, January 21, 1923; “To Build Brick Residence,” The Daily Star, February 17, 1915; Building Residence for Dr. G. B. Harrison,” The Free Lance-Star, February 27, 1929; “Eight Fredericksburg Homes open their doors,” The Free Lance-Star, December 1, 1979.

[23] “New Houses To Be Built,” The Daily Star, July 1, 1910; “To Build Residence,” The Free Lance-Star, January 8, 1916; Richard Guy Wilson et al., “J. Conway Chichester House,” Society of Architectural Historians, SAH Archipedia, accessed January 31, 2025, https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/VA-01-FR50; “Will Build Bungalow,” The Free Lance-Star, July 9, 1910; “Fredericksburg, VA. – Bungalow,” The American Contractor, July 29, 1916, volume 37, 94.

[24] “Bowling Green High School,” The Daily Star, July 10, 1912.

[25] “Letter of School Board,” The Free Lance-Star, May 12, 1917.

[26] “Mullen & Mullen,” The Free Lance-Star, December 21, 1922; “Will Erect Handsome Building,” The Daily Star, July 23, 1918; “Sunshine Laundry Is To Begin Operation Monday,” The Free Lance-Star, March 15, 1929.

[27] “City Items,” The Free Lance-Star, May 09, 1930; “City Items,” The Free Lance-Star, May 21, 1935; “Find Shattered Rafters In Repairing Old Tavern,” The Free Lance-Star, March 29, 1938, “To Build $20,000 Residence,” The Free Lance-Star, May 12, 1917; “New Home of Planters National Bank,” The Free Lance-Star, October 8, 1926; “Renovating Country Club,” The Free Lance-Star, March 12, 1925; “To Erect New Building,” The Free Lance-Star, July 8, 1924, “Bank and Office Buildings,” Manufacturers’ Record, April 14, 1910, 65, accessed January 31, 2025.

[28] “The Hospital Addition,” The Daily Star, May 13, 1910; “The Hospital,” The Free Lance-Star, June 10, 1915; “News of Bygone Days,” The Free Lance-Star, March 29, 1933; “Hospital Work is Under Way,” The Free Lance-Star, September 23, 1927.

[29] “Contract Awarded,” The Daily Star, July 19, 1916; “New Hope Church,” The Free Lance-Star, June 9, 1915; “To Build New Chapel,” The Daily Star, September 4, 1914.

[30] Stern also designed a chapel “near Truslow’s Store” in Stafford although at the time of this article, the location has not been determined. “To Build Chapel,” The Daily Star, September 19, 1910; “Improvements for Warsaw,” The Free Lance-Star, May 13, 1919; “Completing Improvements,” The Free Lance-Star, May 21, 1925.

[31] “Will Have Handsome and Modern House,” The Free Lance Star, November 2, 1911; “The “Snowden” Fire,” The Free Lance Star, January 19, 1926; “Hayfield Mansion,” The Daily Star, November 11, 1911; “Will Close Mary Washington Home,” The Free Lance-Star, August 17, 1929.

[32] “Kiwanis Held Informal Session,” The Daily Star, March 17, 1926.

HFFI comments to Planning Commission on Railroad Station Overlay (RSO)

/in Uncategorized /by Danae Peckler

The area immediately south of the railroad is featured in some of the most famous photographs of Fredericksburg during the Civil War. What do you think new construction in this area look like?

6 December 2024

Dear Planning Commissioners and City staff:

Historic Fredericksburg Foundation, Inc. (HFFI) respectfully asks that the Planning Commission defer action on removing the Railroad Station Overlay District (RSO).

The recent staff presentation did not provide much context for the establishment of the RSO, the factual basis on which it was created, nor why its “failure” seems solely predicated on recent adaptive re-use projects of existing historic buildings. The primary point made was that parcels were removed from the district for past projects and should therefore, be removed from the entire covered area. Staff’s presentation did not discuss that these projects involved the rehabilitation of historic properties—the driving factor in the removal of these parcels from the RSO. The historic preservation component of these projects was used to justify their exemption.

The city’s preservation goals have long supported the adaptive re-use of existing historic buildings. State and federal governments along with the universal building code also enable special exemptions and greater flexibility in support of the adaptive re-use and preservation of the built environment. Thus, it is unsurprising that these particular projects were “grandfathered” out of current zoning.

Before changing zoning, a substantive and thorough explanation of why such an alteration is needed, why the existing zoning is having undesirable effects or failing to meet city goals, and how the proposed changes is expected to meet stated new goals should be clearly presented to the public.

During works sessions and meetings, a majority of City Council members have indicated that density and height restrictions throughout the city needed to be increased. It was made clear that this included the Old and Historic Fredericksburg Overlay District (OHFD). The area around the train station has been specifically mentioned by council members for more intensive residential development. Discussions have also occurred among some on council who are not prepared to support the city’s goal of establishing Neighborhood Conservation Districts (NCD) to preserve the distinct features of our city unique as it runs contrary to their height and density goals.

These discussions represent significant changes in the city’s goals to maintain Fredericksburg’s unique and historic character. And these discussions have occurred without any community engagement at work sessions and retreats.

Before considering any further changes affecting the OHFD, City Council needs to clearly articulate their height and density goals across the community and engage directly with the public to better understand the level of community support for those changes. This is especially pertinent around the train station after the recent derailment. Residents in the immediate vicinity of the rail line have voiced concerns with the City’s position that the OHFD will, “ensure an appropriate transition is maintained in the Train Station District.”

Staff presentation at your November 13th meeting referenced the proposed 400 Princess Anne Street project as a successful example of the OHFD’s protections, yet failed to mention City Council’s vote to deny a special permit to this project because it did not meet OHFD goals and design guidelines. Has any internal review of this project or process been conducted following the council’s vote? Might such a review be completed before further zoning changes are made to clarify potential impacts and expectations for future development in the immediate area and OHFD?

HFFI strongly recommends that the Planning Commission delay any action on the RSO until the “failure” of the RSO is clearly articulated. While the guiding principles of the RSO seem at odds with current thinking of City Council, the concerns of impacted area residents, members of the public, members of the Architectural Review Board, and council’s voting record provide sufficient cause for further review of this matter to ensure community support going forward for increased density and building height in the city and especially in the OHFD.

We sincerely thank you for your consideration of this issue, and for all you do to ensure the stewardship of Fredericksburg’s cultural historic landscape for residents and property owners–past, present, and future.

Sincerely,

David James, President

Historic Fredericksburg Foundation, Inc.

Infill & Teardown Statistics in FXBG

/in Uncategorized /by Danae PecklerCity of Fredericksburg Planning staff made a presentation at the August 28, 2024 meeting of the Planning Commission on the amount of infill development and teardowns in town over the past few years (a copy of staff’s memo and presentation is available at the end of this post). HFFI was pleased to see that City staff conducted such an analysis and hopes they will continue to keep the public informed on this matter – as it provides insight into potential gentrification and loss of historic housing in some of the City’s older established neighborhoods. HFFI’s public comments read at the meeting are provided below.

The Historic Fredericksburg Foundation has reviewed the upcoming agenda for the August 28, 2024, meeting of the Planning Commission and submits the following comments on select items:

Discussion of Potential Policies, Ordinances or Applications: Item 5.A. Analysis of Tear Down and Infill Housing

HFFI is pleased to see staff’s assessment of recent teardowns and infill development and are thrilled to see the long-standing historic trend of infilling vacant lots continue in our community. We also understand that the demolition and replacement of some older buildings is necessary for the continued growth and development of the city. The buildings constructed today and those erected decades ago will not last forever. Regardless, what we choose to preserve and what we discard is a direct reflection of our culture and community values.

The adaptive re-use and rehabilitation of existing buildings is important for many reasons, some of which are not commonly known.

- Environmental Benefits: Reusing buildings and making them more energy efficient plays an essential role in meeting our community’s goals for sustainability, resilience, and climate action. Modernizing existing buildings greatly reduces greenhouse gases by keeping many tons of material out of landfills and reducing the need for new construction, which typically generates far more carbon emissions than conservation and reuse.

- Economic Benefits: Repairing, reusing, and renovating historic places keeps money in the local economy by spending more on labor than materials compared to new construction, and employing local laborers. Furthermore, the rehabilitation of older buildings gives property owners a marketing edge—with buyers paying a premium for the resource’s unique features and stories.

- Health & Well-Being Benefits: Older places also support our emotional and psychological health in multiple ways. We form strong emotional bonds with the places that helped shape us or that provide the backdrop for our daily lives, and we take comfort in their familiarity. Older and historic places remind us that we’re part of something bigger than ourselves, connecting us with our past and with each other, while fostering a sense of belonging and pride of place in our community.

- Blight Reduction Benefits: Reviving vacant and underused buildings, maintaining older multifamily housing, and adding compatible new construction in older neighborhoods can add density and vitality to a community while keeping what makes it unique.

- Affordability Benefits: Most of the country’s existing affordable rental housing is unsubsidized, privately owned, and at risk. New construction can’t keep up with demand, and the vast majority of new construction isn’t affordable to low- and middle-income residents. Rehabilitating our existing housing stock keeps these buildings safe and maintains greater affordability at a fraction of the cost of new construction.

Infilling vacant lots is the most organic way a city grows new built resources. The other way involves the demolition and replacement of older structures or buildings of lesser market value. While HFFI is pleased staff’s study highlights just four of the 14 new houses in 2024 resulted in the demolition of older buildings, it is both common sense and proven fact that vacant lots are low hanging fruit. As time goes on, Fredericksburg neighborhoods will increasingly lose their older, smaller, and more affordable housing.

The fact that new buildings raise the property value of the existing parcel is made clear in staff’s analysis. This infill will also impact the value of neighboring properties—good news to many homeowners whose residence is likely their largest financial asset. Sprinkled across the city in various neighborhoods, incremental increases in property value enhance the wealth of our community slowly over time. However, such changes also increase property taxes—impacting some people and neighborhoods at higher rates than others. Given Fredericksburg’s ongoing challenges of affordability, rising cost of living, and the forecasted growth in renter-occupied houses, investor-driven rapid growth in our older established neighborhoods can only exacerbate these issues.

Preservation isn’t the sole solution to pressing local issues, but we can’t solve them without it. We can’t build our way out of the housing crisis or bulldoze our way out of climate change. We need to use every tool we have, including our existing places and infrastructure.

Hired consultants and planning experts like Streetsense and Heritage Arts have repeatedly advocated for increasing local preservation incentives—a priority task for City Council since 2021—to encourage the conservation and rehabilitation of our existing housing stock. We can support preservation and new development simultaneously—it is not either or, it’s both.

HFFI hopes that the Planning Commission and City staff will continue to assess the quality of infill and impacts of teardowns in the City, sharing these statistics regularly with the public to monitor character loss and any rise in gentrification. We further urge Planning Commissioners to support the expansion of preservation incentives to retain and rehabilitate our unique, authentic, historic, and most affordable housing assets.

Cecil L. Reid: Engineer of Hydro-Electric Plants, Pragmatic Houses, & City Council

/in Uncategorized /by Danae Pecklerby Professor Michael Spencer, Department of Historic Preservation, University of Mary Washington

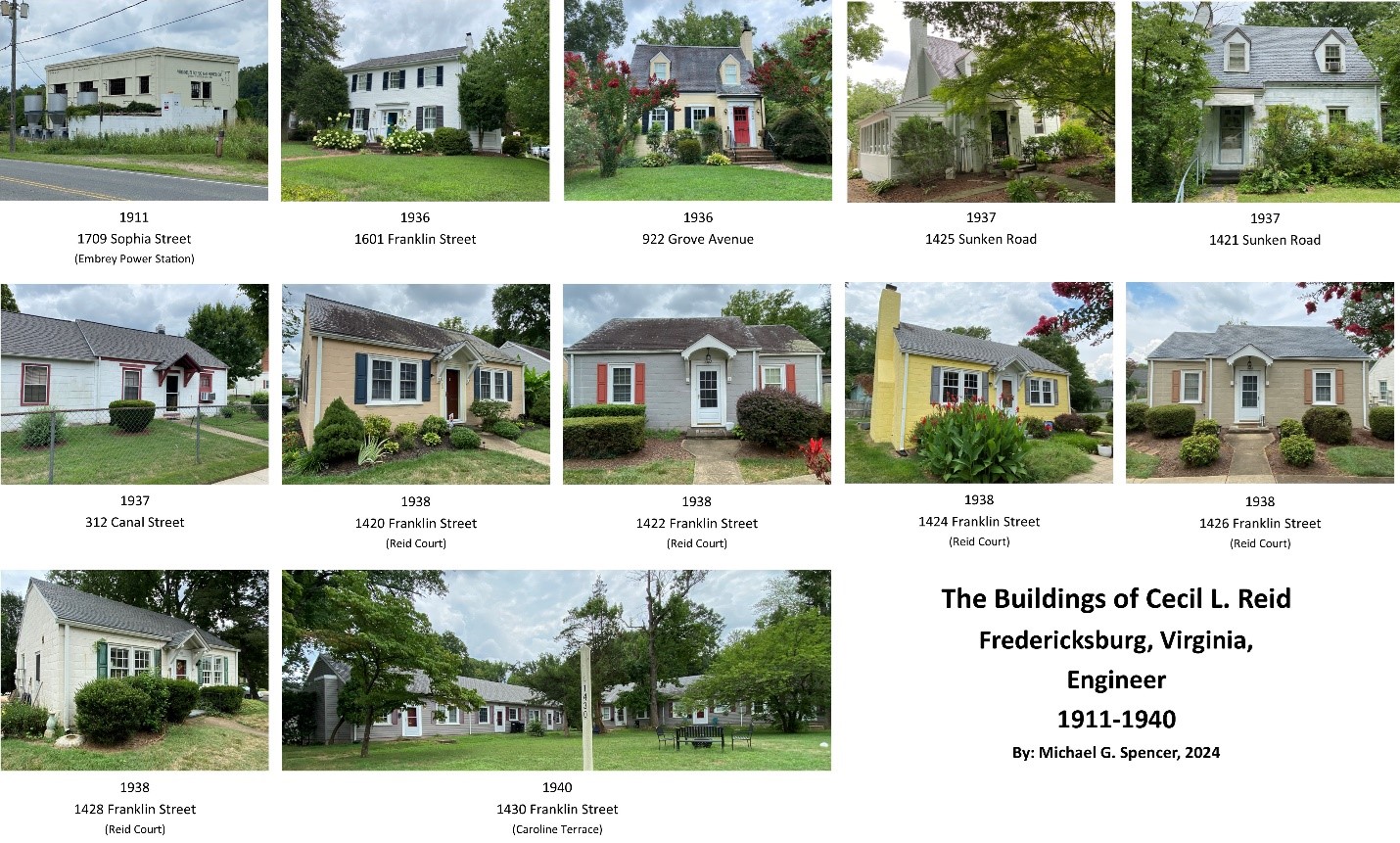

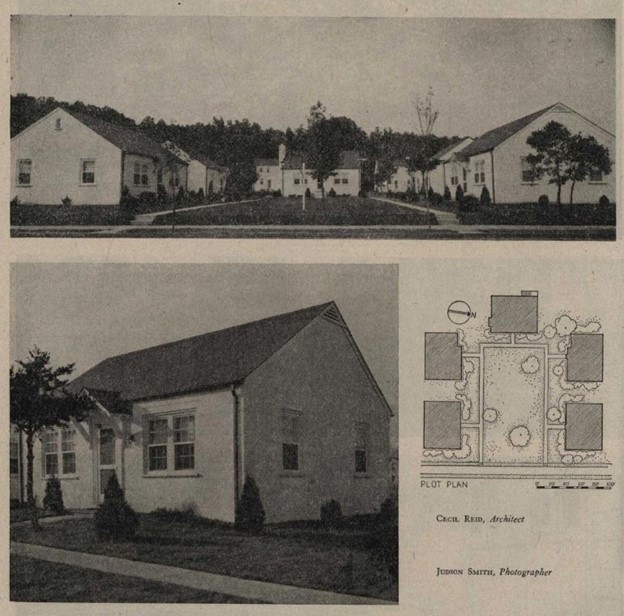

Fredericksburg, like many communities in the early to mid-20th century, saw a significant number of concrete houses constructed. Cecil Latta Reid, although not the most prolific builder in the community, was responsible for the design and construction of at least 11 of these, mostly in the College Terrace neighborhood. His pragmatic design approach seemed to appeal to the 1930s mindset, so much so that his 1938 Reid Court development was noted in The Book of Houses, a 1946 publication by John Dean, Regional Economist of the Federal Housing Authority, and Simon Breines, an architect with the New York firm Pomerance & Breine.[i]

However, Reid designed houses only late in his career. His primary work centered on design and construction of hydroelectric plants throughout the South.[ii] The engineering of such early electric works was a job well-suited for Reid, who was noted as “hard driving and relentless” as well as “exact and precise.” A later description saw him as always carrying a slide rule and collapsible steel tape “which he uses at the slightest provocation.”[iii] No doubt Reid’s strong work ethic was, in part, a necessity. Born in 1882 in Rock Hill, South Carolina, Reid lost both his parents, Samuel and Frances, by the time he was 18 years old.[iv] Despite this hardship, he enrolled at Clemson University in 1899 and worked his way through the mechanical engineering program by tutoring, drafting, and working in the dining hall. Even with these jobs, Reid still graduated in 3 years at the age of 20.[v] Clemson would continue to feature prominently in Reid’s life after graduation. He dedicated significant time and resources to the university, including establishing the Baskin Loan Fund in honor of his mother.[vi] Clemson awarded him two honorary degrees, one in 1928 and another in 1953.[vii]

Upon graduation, Reid began working for the Seaboard Air Line Railway where he became acquainted with William C. Whitner of Richmond, Virginia. Whitner by this time was known as a pioneering “waterpower development engineer of the South.” That apparently appealed to Reid, because he began working with Whitner shortly thereafter. The work eventually brought him to Fredericksburg in 1906 where Frank Jay Gould employed him to survey the Rappahannock River and its potential use for hydro-electric power generation. On the basis of Reid’s survey, Gould purchased the old Fredericksburg Power Company and proceeded to finance the construction of a new dam and power plant. Both new structures were designed by Reid, who served as the Resident Engineer under the guidance of his mentor, Whitner.[viii] Work on the dam, later called the Embrey Dam, was completed in August 1909.[ix] In April of the same year, plans for the power plant had been completed and construction began the following year, culminating in 1911 (Figure 1).[x] Although the use of reinforced concrete was a significant departure from traditional Fredericksburg building materials, similar design and construction techniques had been used a few years earlier in the construction of the James River Power Plant located on Belle Isle in Richmond, Virginia.[xi] Reid would go on to design and oversee construction of a number of such power plants, including Virginia Western Power Company’s plant at Balcony Falls in Rockbridge County, Virginia, in 1916.[xii]

When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, Reid enlisted and was appointed Chief Construction Engineer at Camp Bragg (now Fort Liberty) in North Carolina.[xiii] After the war, he continued to design and build hydroelectric plants, although he also dedicated significant time to community service, stating that “every citizen should put public duty above self for it is through this that we can better our community and make the world a bit better for our having existed on it.”[xiv] Reid’s community service included chairing committees to erect two new school buildings in Fredericksburg, creating the Department of Manual Training at Fredericksburg High School (now James Monroe High School), serving as President of the Fredericksburg Building and Loan Association, and eventually serving 9 years on City Council (1933–1942). Despite these accolades, Reid was not driven by the need for power or recognition, expressing in his run for City Council that he was willing to “serve if the citizens wanted him but…if it was a matter of personal preference he would decline the offer.” At the time, Reid was elected to Council with the highest number of votes ever obtained in a contested election—despite never asking for a vote—a testament to his ability and character.[xv]

During his service on City Council, Reid began to design and build a series of homes located in the Kenmore subdivision of the College Terrace neighborhood. Although he was not new to real-estate investing—having bought and sold a number of lots in Fredericksburg—designing and building homes was new ground. Building permits were issued to Reid on the first three houses he designed in 1936—906 (later 918) Grove Avenue, 922 Grove Avenue, and 1601 Franklin Street. The latter, 1601 Franklin Street—ultimately was the most expensive house he would design and build, with a permit value of $4,500—would be a significant departure from his other house designs.[xvi] Designed as a Colonial Revival residence, the two-story central passage building used brick laid in a stretcher bond, whereas Reid’s other houses would employ concrete block, including both 906 and 922 Grove Avenue.

The use of concrete block had advantages over brick at the time, primarily in terms of reduced construction time and cost. With the country still emerging from the Great Depression, cost was a major consideration and would factor into all of his subsequent designs. Concrete was also a material that Reid was quite familiar with, having used it in his hydroelectric plants since the early 1900s. Despite this familiarity, the construction of 922 Grove Avenue, when compared with his later concrete block buildings, suggests that Reid was experimenting to some degree. Rather than laying the concrete block in a stretcher bond pattern, a smaller course of concrete block was inserted every other course, creating an interesting aesthetic. Although this configuration of concrete block appears to be unique to 922 Grove Avenue, slate roofing and cast concrete lintels, with shallow recessed panels, appear in virtually all of his later buildings. Both 906 (918) and 922 Grove Avenue were designed with a Tudor Revival aesthetic, incorporating asymmetrical fenestration and projecting front entries, with 922 Grove Avenue even incorporating a “kick” at the eave. Scroll work was also included in a wood panel above the fixed picture window at 906 Grove Avenue and the door surround at 922 Grove Avenue.

Figure 2: 922 Grove Avenue. Note the cast concrete lintel above the window with recessed panel as well as the scrollwork on the door surround. Close examination of the concrete block walls shows the interesting bond pattern of one course of full-sized block followed by a course of ½ sized block.

Permits were issued for 1421 and 1425 Sunken Road as well as 312 Canal Street the following year. Both Sunken Road houses also incorporated the Tudor Revival aesthetic, with 1425 Sunken Road even using the same door surround as 922 Grove Avenue. However, 312 Canal Street employed a less stylized aesthetic consisting of a symmetrical fenestration with three-bays and a central entry that was covered by a small gable roof supported by brackets on either side. The size of the building was also reduced, resulting in a more cost-effective residence with a permitting value of $1,200, significantly less than Reid’s earlier houses.[xvii]

During the summer of the following year, Reid began construction of Reid’s Court, located at 1420–1428 Franklin Street.[xviii] With 312 Canal Street serving as a model, five concrete block houses were erected using three similar plans. Both 1420 and 1428 Franklin Street were perhaps the most similar in design to 312 Canal Street. The only difference was that both 1420 and 1428 incorporated paired windows within the bays flanking the central entry. Located at the end of the U-shaped “cul-du-sac,” 1424 Franklin Street followed a similar design but with an exterior end chimney. The two houses at 1422 and 1426 Franklin Street offered the most variation. Still three-bays wide, the buildings were asymmetrical owing to the west bay of both buildings being recessed. Otherwise, the buildings incorporated many of the same design aesthetics as the other buildings constructed at Reid’s Court. Collectively, the 1938 building permits noted the value of the project at $7,000, approximately $1,400 each, comparable to 312 Canal Street. The individual design aesthetic of these houses was critiqued by John P. Dean and Simon Breines, authors of the 1946 publication, The Book of Houses. With 1426 Franklin Street as an example, the authors compared Reid’s design with mid-century modern aesthetics noting that in:

“…small homes of traditional style such as above [1426 Franklin St.], the windows are little holes knocked in the wall at even intervals. In the modern small house…windows are grouped to admit lots of light at well planned points.”[xix]

However, the authors went on to extol the virtues of the larger five-house development, of which 1426 Franklin Street was a part, noting that individually, the houses were “undistinguished”:

“…by combining them in a pleasing neighborhood plan, the group takes on a character which the individual house does not possess. And a neighborhood of this sort has many advantages in livability which go far beyond the mere pleasant appearance of the structures. With land as plentiful as it is in the United State and with the raw land comprising such a small part of the total cost of a completed house, we may ask ourselves why all our neighborhood developments are not so intelligently planned and constructed as the one shown above.”[xx]

Figure 4: Images from the 1946 publication, The Book of Houses, by John Dean and Simon Brienes. Note the courtyard created by the buildings which are oriented toward the green space and not Franklin Street.

Although novel to Fredericksburg at the time, the idea of a planned courtyard neighborhood, albeit small in scale, echoed aspects of the larger Garden City movement. Begun decades earlier in the early-20th century but popularized in the United States in the 1920s through developments such as Radburn, New Jersey, the movement emphasized affordability as well as interaction with green spaces. Both developments, while vastly different in scale, created neighborhood courtyards that provided residents with community green space free of automobiles, which were relegated to the street or rear of the development.

In 1940, 2 years after completing Reid’s Court, Reid began construction of Caroline Terrace, named after his wife.[xxi] Located at 1430 Franklin Street, adjacent to Reid’s Court, Caroline Terrace consisted of two cinderblock structures each with three units. These units were similar in appearance to Reid’s earlier standalone residences, such as 312 Canal Street, but with some window variations. Like Reid’s Court, Caroline Terrace faced a large communal green space with parking at the rear of the lot accessed via an alleyway. While the houses remained affordable, quality materials, such as slate roofing, were used in construction.

Reid would contract with W.T. Courtney in 1948 to extended his garage on Cornell Street, but the Caroline Terrace development was his last residential project.[xxii] Reid died 7 years later in September 1955.[xxiii] Despite the small number of homes built, his contribution to the College Terrace neighborhood was significant, and he was noted at the time as introducing “some architectural and construction features which have been most pleasing as well as practical.”[xxiv] This contribution is especially noticeable along the 1400 block of Franklin Street, where his homes still help define the area’s character. Also noteworthy are the economical designs he used, which when coupled with the introduction of quality materials and green space, serve as one of Fredericksburg’s few noteworthy references to the interwar (1918–1939) Garden City planning movement.

Endnotes:

[i] Dean, John and Simon Brienes, The Book of Houses (New York: Crown Publishers, 1946), 28–9, 58.

[ii] Free Lance-Star, September 6, 1955, 3:3.

[iii] Free Lance-Star, June 1, 1938, 6:4.

[iv] The National Archives At St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; Record Group Title: Records of the Selective Service System; Record Group Number: 147, accessed August 2024, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/1210104:1002?tid=&pid=&queryid=de623f72-96cb-428d-ac2d-fd51c49bd2e3&_phsrc=MjY1&_phstart=success Source; Free Lance-Star, June 1, 1938, 6:4.

[v] Free Lance-Star, June 1, 1938, 6:4.

[vi] The Newberry Observer, September 6, 1955, 2:5.

[vii] Free Lance-Star, June 13, 1953, 3:5.

[viii] Free Lance-Star, September 6, 1955, 3:3.

[ix] Engineering Record, vol. 61 no. 7, (New York: McGraw Publishing Co, 1910): 197–8.

[x] Electrical Review and Western Electrician, (March 20, 1909): 549; The Free Lance, May 20, 1911, 1:4.

[xi] Street Railway Journal, vol. XXIII no. 1, (New York: McGraw Publishing Co., 1904): 20.

[xii] Rockbridge County News, vol. 32 no. 36, (July 6, 1916): 3:5.

[xiii] Free Lance-Star, September 6, 1955, 3:3.

[xiv] Free Lance-Star, June 1, 1938, 6:4.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Fredericksburg, Virginia Building Permits, 1936.

[xvii] Fredericksburg, Virginia Building Permits, 1937.

[xviii] Fredericksburg, Virginia Building Permits, 1938.

[xix] Dean, John and Simon Brienes, The Book of Houses (New York: Crown Publishers, 1946), 58.

[xx] Dean, John and Simon Brienes, The Book of Houses (New York: Crown Publishers, 1946), 28–9.

[xxi] Fredericksburg, Virginia Building Permits, 1940.

[xxii] Fredericksburg, Virginia Building Permits, 1948.

[xxiii] Free Lance-Star, September 6, 1955, 3:3.

[xiv] Free Lance-Star, June 1, 1938, 6:4.

“The Most Historic Park in America’s Most Historic City”

/in Uncategorized /by Danae Pecklerby Danae Peckler, HFFI Preservationist

On the first page of his 1991 book, Robert A. Hodge called Alum Spring Park, “the most historic park in America’s most historic city.” These days, people might view that ambitious moniker with suspicion. However, the more one learns about Fredericksburg’s past, the more remarkable it becomes. The park encompasses 34.75 acres around the Alum Spring—named for the crystalized salts that form on the surface as the spring’s water evaporates. However, the area has also served many other purposes:

- A source of clay for local indigenous populations that camped along area waterways

- The site of multiple 18th and 19th century grist and saw mills along with millworker houses

- A hospital and prison camp for Hessian and British soldiers marched to Fredericksburg after Cornwallis’ surrender in October 1781

- A place for dueling and more than a few tragic deaths

- A quarry for local sandstone

- A place of refuge and conflict during the Civil War, as well as the site of many veteran reunions into the 20th century

- A plentiful source of ice in the winter

- A popular local swimming hole in the summer

- A wondrous place to explore the area’s natural and cultural history.

Local newspapers and long-time residents credit Hodge—a geologist, educator, and local historian—as the galvanizing force behind the creation of Alum Spring Park. After moving to Fredericksburg for a teaching job at James Monroe High School in 1956, Hodge began taking students to Alum Spring to illustrate the area’s natural history, using its diverse rock formations, from the bed of Hazel Run to its sandstone cliffs, as visual aids for teaching geologic time. And for the many decades that he lived here, Bob Hodge also read, thoroughly researched, and wrote about local history in his spare time. Decades after his efforts to create Alum Spring Park, he published a small book about the property, entitled A History of Alum Spring Park, to chronicle all that makes it unique and historically significant (copy available at the CRRL Downtown branch).

The area was actually first proposed as a park by the Fredericksburg Development Company and appears in the firm’s 1891 map of holdings in and around the city. However, the idea for a public park did not come to fruition until the land was threatened by a large townhouse development in the mid-1960s. The Planning Commission and Recreation Commission supported the park idea, and in October 1965, Fredericksburg City Council voted unanimously to purchase the land that comprises Alum Spring Park today (The Free Lance-Star, Oct. 6, 1965:4).

The city’s Recreation Commission, of which Bob Hodge was a member, made a careful study of the 34.75-acre property in consultation with National Park Service staff and state Outdoor Recreational Department officials. In December 1967, a formal report made to the City Council “emphasized the primary purpose of the park was to preserve the natural state of the tract as much as possible,” and provided a plan for the park’s immediate development along with some long-range proposals (Hodge 1991:39).

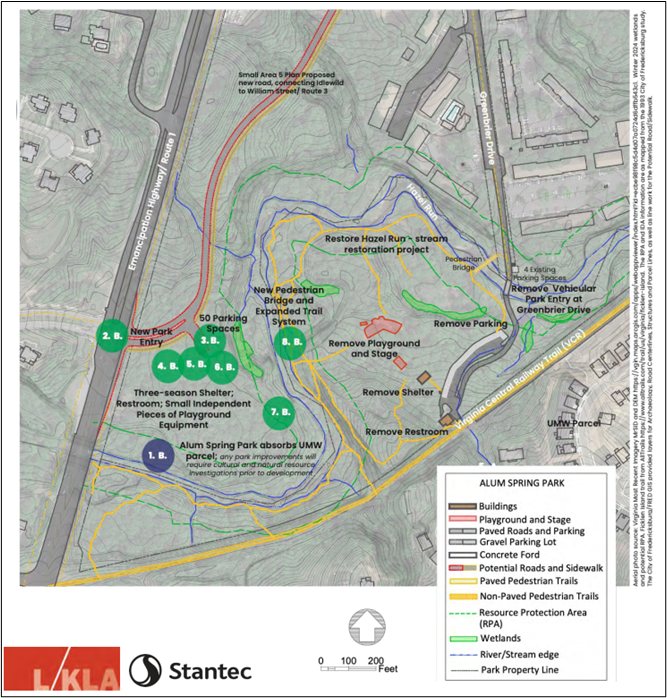

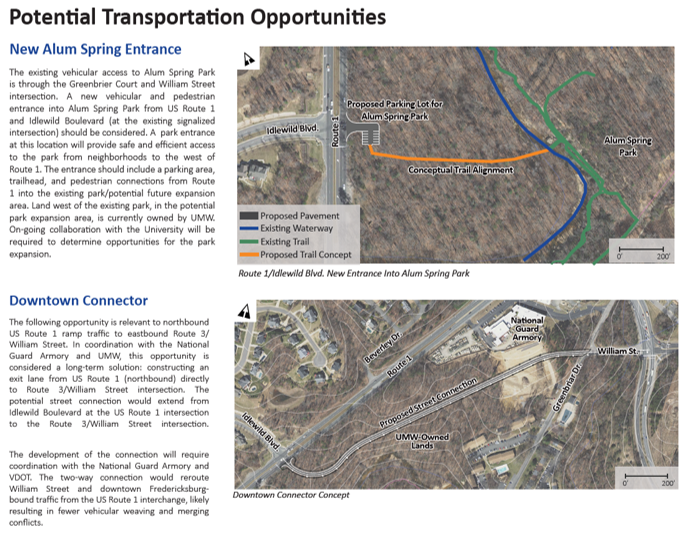

Presently, two planning efforts stand to substantially affect the landscape within and around Alum Spring Park—both require and assume that the city will acquire the neighboring 34-acre tract of woodland on the east side of Emancipation Highway, north of the park, from the University of Mary Washington (UMW).

The Parks & Recreation Master Plan currently proposes a wholesale redesign of Alum Spring Park, reorienting it toward the busy Emancipation Highway (Route 1). This plan calls for closing the ford entrance and removing most of the existing facilities to build a new larger parking lot, bathroom/ welcome center, and playground on UMW’s undeveloped land (Figure 1). Simultaneously, the Small Area 5 plan currently proposes the construction of a new “connector road,” extending from the William Street/Blue & Gray Parkway (Route 3) intersection to meet with Idlewild Drive or Beverly Lane (Figure 2).

City staff’s proposed plans to build a new roadway with a multi-use path, 50-space parking lot, new welcome center/restroom facility, picnic shelters, and a playground on UMW’s forested tract seems to be at odds with many stated environmental and historic preservation goals.

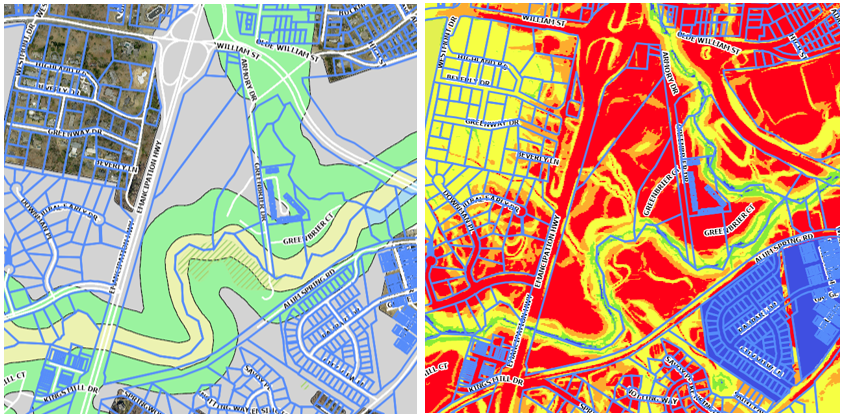

Given its proximity to Hazel Run and Alum Spring, much of Alum Spring Park and UMW’s wooded 34 acres are located within “Resource Protected” and “Resource Management Areas” under the Chesapeake Bay Protection Program. The rest of UMW’s parcel is within the “Whole Lot Provision” of the Resource Management Area (Figure 3). Both the Alum Spring and UMW tracts have also been identified in George Washington Regional Commission (GWRC) reports focused on bettering our environment. In the Green Infrastructure Regional Plan, both parcels are identified as Contributing Eco-Core areas, and “the over-arching finding is that proper forest retention can provide important water quality benefits to the Commonwealth and Chesapeake Bay Watershed,” based on recent studies on the impact forest buffers have in protecting against erosion and stormwater runoff (GWRC 2016, 2017).

From a preservation perspective, these plans will have a negative effect on known cultural historic resources. The 1968 Recreation Commission report to the City Council called for archaeological investigations at one of the known mill sites; however, few, if any, such studies have been conducted. The area also has a significant indigenous, Colonial, Civil War, and industrial history—much of which has yet to be thoroughly documented and analyzed. Localities and other state agencies often avoid disturbing areas known to contain important cultural artifacts, embracing the cheapest option, which is to preserve them in place. Given that almost every inch of the UMW and Alum Spring Park tracts falls within the highest probability in the City’s Archaeological Predictive Model, both plans will come at a higher price to taxpayers (Figure 3).

It is often said, “history repeats itself” and “no idea is ever new.” In 1980, a proposal for a new road connecting the end of Alum Spring Drive to the Route 1 Bypass was voted down by City Council after an uproar from local groups, including “the Jaycees, the Planning Commission, Recreation Commission, Economic Development Commission, and the Rappahannock Garden Club,” who “chiefly [opposed the road] because it would border tranquil Alum Spring Park” (The Free Lance-Star, Feb 28, 1980:17). The Public Works Committee had supported the idea as a “trucking link that would open an undeveloped section to business use” (The Free Lance-Star, Jan 25, 1980:3). A January 28, 1980, editorial in The Free Lance-Star addressed the feelings of many residents had for this special place in the city:

Crossing tiny Alum Spring is like entering another century. You may hear a truck on the Bypass or spot the top of a nearby apartment complex. But the distractions are few amid the splendid isolation of Alum Spring Park’s wooded hills.

There is a sense of discovery and reflection to these 35 acres. A 2,000-year-old sandstone cliff and an abandoned railroad bed from a century ago suggest a resistance to change. For close to 40,000 visitors a year, a piece of Fredericksburg’s past has been delicately and beautifully preserved….

With the Fredericksburg area leading Virginia in growth, it has never been more important to safeguard our remaining natural and historical resources from the temptation of short-term economic gain….

The Council should do more than ratify the overwhelming arguments against this proposal. It’s time to go on the offensive in protecting our natural assets. Possible scenic easements on nearby undeveloped tracts should be explored as a way to insulate the Alum Spring “experience” from future developments.

As currently proposed, the “new” plans fail to protect much of what City Council’s Vision for 2036 describes as important to Fredericksburg’s future and identity. They do not preserve one of the few sizable, undeveloped, Eco-Core areas in the City; do not reduce run-off into our waterways; do not protect known cultural historic resources; and do not appear to make prudent use of taxpayer dollars.

Contact Us

Historic Fredericksburg Foundation, Inc.

Physical Address:

1200 Caroline Street

Fredericksburg, VA 22401

Mailing Address:

PO Box 458

Fredericksburg VA 22404

540-371-4504

office@hffi.org