Architect Philip Stern’s Life and Architectural Legacy in Fredericksburg

by Inga Gudmundsson McGuire

A shorter version of this article was published in the April 2025 issue of Front Porch Magazine.

In and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, architect Philip Nathaniel Stern’s legacy sits in plain sight. On streets like Caroline (previously Main), Washington Avenue, and William (Commerce), his oeuvre includes numerous public buildings that anchor downtown Fredericksburg occupying corner lots and coveted plots of land. From his office in the Law Building (910 Princess Anne Street) from 1909 to 1949 (at least), Stern supplied Fredericksburg, neighboring counties, Winchester, Richmond, and far-flung states such as Mississippi and New York, with his architectural expertise and knowledge. Many of his completed designs, both commercial and residential, are extant to this day. While extensive research continues on the life and work of Philip Nathaniel Stern (1878–1960), an overview of his architectural career in Fredericksburg, which spanned four decades, is laid out below in hopes that more interest and discovery into Stern will be sought out in the future.

Philip Nathaniel Stern was born, along with his twin sister Katharine Wyman Grumell (nee Stern), on April 15, 1878, in Bangor, Maine. His parents, Jacob Stern (1844–1913), a German-born merchant married Maine native, Eunice Wyman Walker (1848–1924), in December 1876.[1] The Sterns operated a store aptly named Stern & Co. from 1871 until 1887, which featured fine goods.[2] A mainstay in Bangor, Stern & Co. remained opened until 1887 when it appears Jacob Stern fell into debt and declared bankruptcy, prompting Jacob and Eunice to move their young family to Karlsruhe, Germany, Jacob Stern’s hometown.[3]

Archival resources in the United States offer scant information about Philip Stern’s childhood in Germany or his eventual return to this country. At the age of eighteen, Philip Stern enrolled in the architecture program at the Royal Technical University of Karlsruhe, now the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, in the winter of 1896 where he studied for the next three years.[4] The first documentation that Stern was back in the United States following the family’s trans-Atlantic move came in June 1901.[5] Two years after leaving school, Stern, now a 23-year-old young man, was working as a draughtsman in Chicago, Illinois, for the well-known D. H. Burnham Co. architectural firm.[6] Stern’s stint in Chicago, however brief, came at an exciting time in the city’s history, following the city’s post-1871 fire which sparked rebuilding and growth. The young draughtsman would have been surrounded by new technological advances, materials, and thought, dictating the changing architectural styles of Chicago in the latter half of the nineteenth century from Richardsonian Romanesque to Beaux Arts. Stern’s introduction and immersion into the Chicago School along with his architectural degree provided a strong foundation for his future career in Fredericksburg.[7]

In the early years of the twentieth century, the fledgling architect led a transient life, traveling between Germany and the United States somewhat frequently. In August 1901, Stern, along with his sister, left New York for Germany on the steamship Vaderland. Almost three years later in May 1904, Stern returned alone to the United States on the Rotterdam, settling in Baltimore, Maryland. Three months prior, in February 1904, a fire destroyed over seventy blocks of buildings in downtown Baltimore, presenting an opportunity for young architects like Stern to help rebuild the city.[8] While working in Baltimore, Stern visited Fredericksburg, Virginia at least twice, in April and December of 1905.[9] That December, he stayed with the prominent Shepherd family, whose patriarch, George W. Shepherd Sr. (1830–1909) was the “leading dry goods merchant” at that time.[10] Soon after his first visit, the “rising young architect of Baltimore” would become inextricably tied to the family and town when, in December 1906, he married one of three Shepherd daughters, the “well known and loved” Mary “Mamie” Glassel Shepherd (1875–1960).[11] Soon after their marriage in Fredericksburg, the newlyweds returned to Baltimore, where Stern continued to work, although research did not uncover any buildings in Baltimore attributed to him.[12]

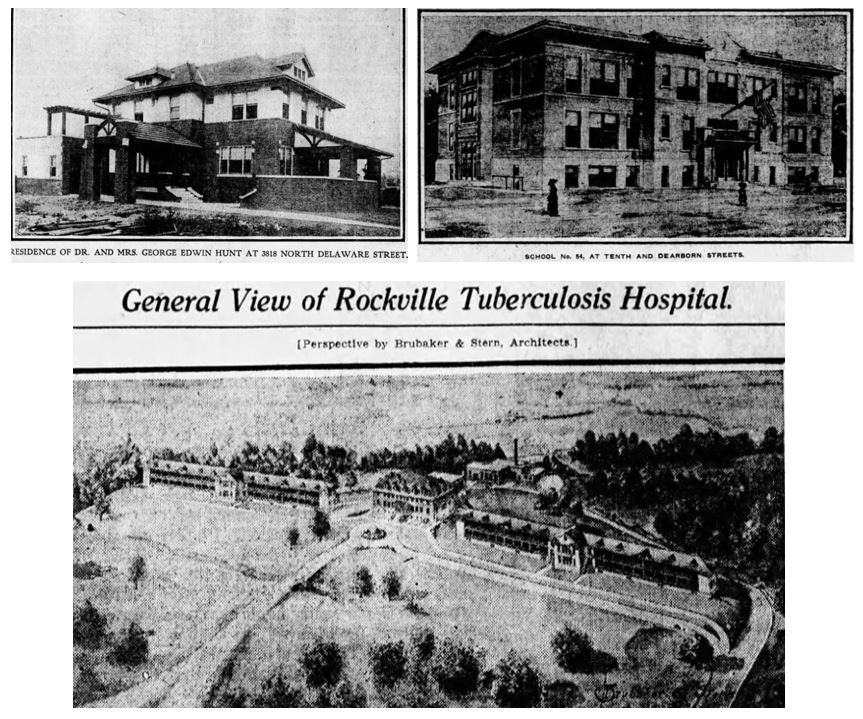

In Baltimore, Stern received a “very lucrative position” to join the architectural firm of Henry C. Brubaker Jr. (1874–1942), in Indianapolis, Indiana.[13] Moving in June of 1907, the Sterns would remain in Indianapolis for two years, Stern quickly becoming an important asset to Brubaker’s firm. In 1908, the two architects formed Brubaker & Stern, successfully winning a variety of large contracts for numerous Indianapolis area projects including the No. 54 School Building (1909), a residence for prominent Indianapolis dentist George Edwin Hunt (1909), and most notably the Rockville State Tuberculosis Sanitorium (1909).[14]

In 1910, Brubaker and Stern added a third architect to their firm, Harry E. Boyle (1881-1947), who operated their Evansville, Indiana office, creating Brubaker, Stern, and Boyle.[15] The firm continued until 1913, when the architects disbanded.[16] By then, Boyle had laid a strong foundation and client base in Evansville and Brubaker had begun to focus his architectural endeavors in Mexico and Texas.[17] As for Stern, once again he would be pulled back to Fredericksburg, this time for good.

While living in Indianapolis, Stern is attributed with designing his first building in Fredericksburg, the former Lafayette School (1908), presently the Central Rappahannock Regional Library on Caroline Street. This anomaly, the only work completed prior to Stern moving to Fredericksburg in 1909, seems somewhat estranged from Stern’s future work in town. The building, which blends both Classical Revival and Romanesque Revival features, is what architectural historian Richard Guy Wilson noted as “more typical of the nineteenth century than of the twentieth” indicating “a lingering Victorian sensibility.”[18] The building’s compound arches, prominent belt course, and corbel detailing above the main entrance do speak to the Romanesque style features that reached the height of their popularity in the decades prior, while the pilasters, pedimented double-hung windows, and central fanlight, seem more aligned with the Classical Revival or Beaux Arts architectural styles, both favored at the turn of the century.

In fall of 1909, Mary and Philip Stern returned to Fredericksburg from Indianapolis following the death of Mary’s father, George W. Shepherd Sr.[19] Whether Stern remained an active partner in business firm with Brubaker and Boyle after this move is unclear, but the architect did embark on his own endeavors in Virginia right away, building a successful architectural business and becoming a well-known architect at both the local and state levels. Stern brought skill and a capable knowledge of architectural design to the growing city of Fredericksburg. Along with his experience working in large metropolitan cities such as Chicago, Baltimore, and Indianapolis, his connections to the prominent Shepherd family and successful completion of the Lafayette Elementary School building created a foundation for Stern’s architectural career in Fredericksburg and surrounding area that only seemed to solidify with time.

In late November 1909, Stern, in collaboration with architects Charles M. Robinson (1867–1932) and Charles K. Bryant (1869–1933), completed plans for the first two buildings of the proposed Fredericksburg State Normal School.[20] Although Robinson is credited with the Jeffersonian Classical Revival style designs for both Monroe Hall (1909–1911) and Willard Hall (1909–1911), Stern superintended the construction of both buildings.[21]

Stern’s institutional, commercial, and residential designs constitute a fair portion of the city’s early-twentieth century landmarks, easily pointed out when driving or walking through downtown Fredericksburg. The architect seemingly pulling from the architectural elements of the colonial and classically adorned buildings around him, applying fanlights, broken pediments, symmetrical facades, dormers and columns to his own original designs at the Princess Anne Building (1910), Commercial State Bank (1911, Crown Jewelers), and the nearby Stafford County Courthouse (1922), as well as the houses at 1304 Washington Avenue (1910), 1111 Prince Edward Street (1914/1923), 407 Fauquier Street (1926), nearby Little Falls on Kings Highway (1915), 804 Prince Edward Street (1923), and 507 Lewis Street (1929).[22]

The Commercial State Bank at the southwest corner of William and Caroline Streets was completed erected in 1910. It has been heavily altered since this ca. 1925 photograph was taken.

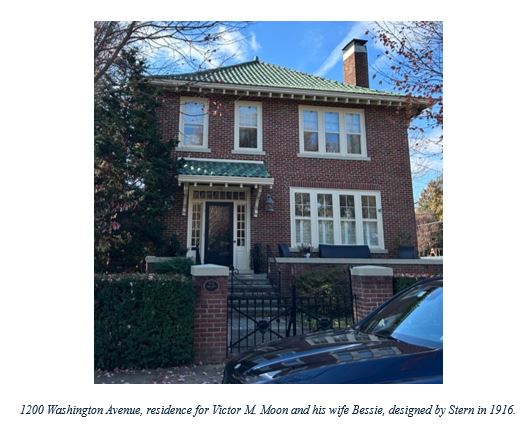

Stern’s residences exhibited other architectural styles popular during the early-twentieth century, some with eclectic elements from the Stick, Craftsman, and Prairie styles. These works include the house at 1307 Washington Avenue (1911), two sister residences at 1308 and 1310 Caroline (1911), 1200 Washington Avenue (1916), and two bungalows built in Stafford County (1910 and 1916, locations for both unknown).[23] Stern’s Lee-Maury School building (1911, demolished) in nearby Bowling Green has Stick-style features like decorative tussles in the gables, wide overhanging eaves, and general applied ornamentation.[24] These buildings, in contrast to the bulk of Stern’s Classical and Colonial Revival designs, showcase the architect’s flexibility and proficiency in providing each client, whether a local businessman or a board of trustees, their desired style and type of building.

His architectural career included a variety of educational and industrial buildings. Along with his early involvement at what is now the University of Mary Washington, the former Lafayette Elementary School, and the Lee-Maury School in Bowling Green, Stern is attributed with designing various other schools in the area, his most impressive school design being the Fredericksburg High School Building, now known as Maury (1919).[25] Some of Stern’s original designs for commercial and industrial establishments are no longer extant, like Sunshine Laundry (1929), Virginia Excelsior Company Office Building (409 Caroline, 1910), the Liberty Cafe Lunchroom and Store (500 Caroline, 1918), and Mullen and Mullen Office (707 Princess Anne, 1922).[26]

He also provided plans for improvements, additions, and interior alterations to existing buildings on streets like William, Caroline, and Princess Anne. Stern directed the interior renovation of the Mansfield Country Club (Fredericksburg Country Club) in 1925, supervised the construction of the Planters Bank Building (1927, now Ava Laurenne Bride), expanded “The Busy Corner” store at 321 William in 1925, and remodeled the Commercial Cafe in the long-demolished Bradford Building (1935).[27] An important legacy of Stern’s is also the numerous alterations he designed for the old Mary Washington Hospital on Sophia Street including additions in 1910, 1915, 1927, and 1933.[28] Stern worked on the interiors of numerous historic houses and landmarks in and around Fredericksburg. Names like Kenmore, Rising Sun Tavern, Mary Washington Home, John Paul Jones House, Sabine Hall in Warsaw, Snowden, Rokeby in King George, Hayfield in Caroline County, and the Knox House (Kenmore Inn) were restored, or rather renovated, by Stern beginning in 1911 when he first worked on Hayfield to his last known restoration work on the Rising Sun Tavern in 1938.[31]

He also provided plans for improvements, additions, and interior alterations to existing buildings on streets like William, Caroline, and Princess Anne. Stern directed the interior renovation of the Mansfield Country Club (Fredericksburg Country Club) in 1925, supervised the construction of the Planters Bank Building (1927, now Ava Laurenne Bride), expanded “The Busy Corner” store at 321 William in 1925, and remodeled the Commercial Cafe in the long-demolished Bradford Building (1935).[27] An important legacy of Stern’s is also the numerous alterations he designed for the old Mary Washington Hospital on Sophia Street including additions in 1910, 1915, 1927, and 1933.[28] Stern worked on the interiors of numerous historic houses and landmarks in and around Fredericksburg. Names like Kenmore, Rising Sun Tavern, Mary Washington Home, John Paul Jones House, Sabine Hall in Warsaw, Snowden, Rokeby in King George, Hayfield in Caroline County, and the Knox House (Kenmore Inn) were restored, or rather renovated, by Stern beginning in 1911 when he first worked on Hayfield to his last known restoration work on the Rising Sun Tavern in 1938.[31]

Stern newly designed a few churches in Virginia, all of which lie outside of the city’s boundaries. St. Paul’s Episcopal Church (1914) in Warsaw; New Hope Church (1915) in Stafford County; and St. Anthony Catholic Church (1916) in King George County are all attributed to Stern. Interestingly, his church designs vary in material and layout.[29] In 1919, Stern also renovated the historic St. John’s Episcopal Church in Warsaw, and in 1925 completed an interior renovation of Fredericksburg’s St. George’s Episcopal Church.[30]

On June 30, 1960, Philip Stern died at the Riverside Convalescent Home, formerly the Mary Washington Hospital on Sophia Street, the same building he had worked on and improved his whole architectural career in Fredericksburg. Philip and Mamie Stern never had children. At the time of their deaths, just a few months apart, their estate was estimated at a staggering $225,000 dollars in 1960, close to $2.3 million dollars in 2025.

This article, neither comprehensive nor extensive, was written in hopes that it would generate more interest and research into architect Philip Stern. His career and legacy, while solidified in Fredericksburg, extends farther into the state and beyond. His restoration work, original architectural designs, involvement in the American Institute of Architects (one of four founders of its Virginia chapter in 1914), Kiwanis Club, and numerous other local and state level committees provides a lens into the architectural profession during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century as well as the development of Fredericksburg and the surrounding area from 1910 to 1960.[32] Only the start of my research into Philip Stern, this article acts as the kickstart into uncovering the architect’s legacy and better understanding his impact on the Fredericksburg area.

Citations:

[1] Bangor Maine Town and Vital Records 1819-1891, 534, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99FP-N4H6?i=533.

[2] “Jacob Stern,” Bangor Daily Commercial, September 30, 1887.

[3] “Bangor and Vicinity,” Bangor Daily Commercial, October 10, 1887″; Jacob Stern Dead”, Bangor Daily Commercial, December 1, 1913; “Philip N. Stern Dead; Retired Architect, 82,” The Free Lance-Star, June 30, 1960; Jacob Stern, Find A Grave, accessed November 10, 2024 https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/253000536/jacob-stern#view-photo=271540071.

[4] Wells, John E., The Virginia Architects, 1835-1955: A Biographical Dictionary, 1997, 430. https://archive.org/details/bwb_T2-ERT-433/page/430/mode/2up?q=stern.;

Matrikel der Gr. Polytechnischen Schule Carlsruhe und der Technischen Hochschule, accessed November 10, 2024, https://digital.blb-karlsruhe.de/blbihd/content/pageview/6635276, 83. Note that Stern’s AIA folder says that he graduated from the program in 1904, which does not match the university’s records found. Matrikel der Gr. Polytechnischen Schule Carlsruhe und der Technischen Hochschule, accessed November 10, 2024, https://digital.blb-karlsruhe.de/blbihd/content/pageview/6635653, 14.

[5] Stern’s parents continued to live in Karlsruhe until Jacob’s death in 1913. Karlsruhe Death Register, Certificate No. 1696, 1913, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/57557:61003?_phcmd=u(%27https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/search/collections/61003/?name=jakob_stern&successSource=Search&queryId=eba5ad5a-2822-43a0-b84a-aabed08be299%27,%27successSource%27). “Welcome to the City of Rockland,” The Bangor City News, June 20, 1901, 2.

[6] 1901 Passport Application, accessed November 10, 2024, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/1096188:1174?tid=&pid=&queryid=3f8117ed-2c80-4196-8ff8-e6bcc895b2fd&_phsrc=Bfa1611&_phstart=successSource; “Philip N. Stern,” The Daily Star, May 5, 1922. Note, that in his passport application, he uses the address of B. B. Thatcher, a prominent Bangor resident who married two of Eunice Stern’s sisters. “Hon. B. B. Thatcher,” Bangor Daily Commercial, June 2, 1906.

[7] Lowe, David Garrad, “Architecture: The First Chicago School”, Encyclopedia of Chicago, accessed December 10, 2024, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/62.html.

[8] Badertscher, Eric, Let’s Take a Look at Maryland, https://research.ebsco.com/c/n4ikcb/viewer/html/65tul2zmdb.

[9] “Newsy Nuggets,” The Daily Star,” April 17, 1905, 3.

[10] “Current Comments,” The Free Lance-Star, December 28, 1905; “Laid to Rest,” The Free Lance-Star, October 7, 1909. Shepherd Jr. served as best man in the Stern-Shepherd wedding, which could be evidence of a close friendship between the two and possible connection to the Shepherd family and Fredericksburg initially. “Shepherd-Stern,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, December 13, 1906.

[11] While researching, the only connection to Fredericksburg, Virginia prior to Stern’s visit in 1905, was a mysterious note in the Bangor Commercial newspaper in 1887. It noted a man, who was thought to be Jacob Stern, had committed suicide in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Called a “sensational report,” to boost newspaper sales, perhaps the Sterns had connections to Fredericksburg that led to this false report.; “Stern-Shepherd,” The Free Lance-Star, December 15, 1906. At the time of their wedding, Mary was thirty-one years old, and Stern was twenty-eight.

[12] “Newsy Nuggets,” The Daily Star, June 17, 1907, 3. Research did not reveal any buildings in Baltimore that Stern designed, or if he was working for an established firm or as an individual architect.

[13] “New Member of Architect Company,” The Indianapolis News,” June 29, 1907, 12.

[14] “Architects Chosen,” The Indianapolis Star, March 27, 1909, 7; “Finish New School Plan,” The Indianapolis Star, August 24, 1909, 14; “How Others Have Built,” The Indianapolis Star, August 22, 1909, 44; ” The P.G.C. and G.E. Hunt Society, Circa 1915,” accessed November 10, 2024, https://images.indianahistory.org/digital/collection/dc013/id/293/.

[15] Marchland, Joan C., Sunset Park Pavilion Nomination, National Register of Historic Places, accessed January 31, 2025, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/132005003.

[16] “Harry E. Boyle & Company Incorporated Architects & Engineers are successors to Brubaker, Stern, and & Boyle,” Evansville Courier and Press, October 26, 1913, 28. It seems that 1913 marks the year Boyle left the firm. Brubaker and Stern continued to work together in some capacity, with a contract awarded to the pair in 1919. “Three Homes Are Started,” The Indianapolis News, July 23, 1919.

[17] “Heads New Architectural Firm,” The Evansville Journal, October 12, 1913, 17; “Gets Mexican Contracts,” The Indianapolis News, February 19, 1910, 2.

[18] Richard Guy Wilson, et. al. “Central Rappahannock Regional Library,” Society of Architectural Historians, SAH Archipedia, accessed January 29, 2025, https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/VA-01-FR32.

[19] “Current Comments,” The Free Lance-Star, October 7, 1909, 3.

[20] “Building Plans Are Approved,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 13, 1909, 2.

[21] “Building Plans Are Approved.”

[22] “Hotel Directors,” The Free Lance-Star, May 31, 1913; “New Residence,” The Daily Star, October 12, 1914; “Commercial State Bank” The Daily Star, May 18, 1912; “Building New Residence,” The Daily Star, July 8, 1925; “New Court House,” The Daily Star, May 9, 1922; “To Build Brick Residence,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, January 21, 1923; “To Build Brick Residence,” The Daily Star, February 17, 1915; Building Residence for Dr. G. B. Harrison,” The Free Lance-Star, February 27, 1929; “Eight Fredericksburg Homes open their doors,” The Free Lance-Star, December 1, 1979.

[23] “New Houses To Be Built,” The Daily Star, July 1, 1910; “To Build Residence,” The Free Lance-Star, January 8, 1916; Richard Guy Wilson et al., “J. Conway Chichester House,” Society of Architectural Historians, SAH Archipedia, accessed January 31, 2025, https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/VA-01-FR50; “Will Build Bungalow,” The Free Lance-Star, July 9, 1910; “Fredericksburg, VA. – Bungalow,” The American Contractor, July 29, 1916, volume 37, 94.

[24] “Bowling Green High School,” The Daily Star, July 10, 1912.

[25] “Letter of School Board,” The Free Lance-Star, May 12, 1917.

[26] “Mullen & Mullen,” The Free Lance-Star, December 21, 1922; “Will Erect Handsome Building,” The Daily Star, July 23, 1918; “Sunshine Laundry Is To Begin Operation Monday,” The Free Lance-Star, March 15, 1929.

[27] “City Items,” The Free Lance-Star, May 09, 1930; “City Items,” The Free Lance-Star, May 21, 1935; “Find Shattered Rafters In Repairing Old Tavern,” The Free Lance-Star, March 29, 1938, “To Build $20,000 Residence,” The Free Lance-Star, May 12, 1917; “New Home of Planters National Bank,” The Free Lance-Star, October 8, 1926; “Renovating Country Club,” The Free Lance-Star, March 12, 1925; “To Erect New Building,” The Free Lance-Star, July 8, 1924, “Bank and Office Buildings,” Manufacturers’ Record, April 14, 1910, 65, accessed January 31, 2025.

[28] “The Hospital Addition,” The Daily Star, May 13, 1910; “The Hospital,” The Free Lance-Star, June 10, 1915; “News of Bygone Days,” The Free Lance-Star, March 29, 1933; “Hospital Work is Under Way,” The Free Lance-Star, September 23, 1927.

[29] “Contract Awarded,” The Daily Star, July 19, 1916; “New Hope Church,” The Free Lance-Star, June 9, 1915; “To Build New Chapel,” The Daily Star, September 4, 1914.

[30] Stern also designed a chapel “near Truslow’s Store” in Stafford although at the time of this article, the location has not been determined. “To Build Chapel,” The Daily Star, September 19, 1910; “Improvements for Warsaw,” The Free Lance-Star, May 13, 1919; “Completing Improvements,” The Free Lance-Star, May 21, 1925.

[31] “Will Have Handsome and Modern House,” The Free Lance Star, November 2, 1911; “The “Snowden” Fire,” The Free Lance Star, January 19, 1926; “Hayfield Mansion,” The Daily Star, November 11, 1911; “Will Close Mary Washington Home,” The Free Lance-Star, August 17, 1929.

[32] “Kiwanis Held Informal Session,” The Daily Star, March 17, 1926.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!