Excerpts from HFFI’s 1996 Candlelight Tour book (The Civil War in This Neighborhood by Erik Nelson) and various marker reports (1310 Littlepage Street report by Jack Johnson; 1317 Franklin Street Report by Richard Hansen).

Land within the residential neighborhood generally known as College Terrace was once part of the 812-acre tract Captain Thomas Hawkins patented from the Crown in 1662. In 1742, half of this tract (406 acres) was sold to Colonel John Lewis, a wealthy merchant who lived elsewhere in Spotsylvania County at the time of this purchase. His son, Fielding Lewis, took up residence on his father’s property adjoining the City of Fredericksburg in the 1740s and began managing the family’s mercantile and shipping business. In 1752, Fielding Lewis purchased an additional 861 acres at the fringes of the town of Fredericksburg. In the decades that followed, Fielding Lewis developed the property into a 1300-acre plantation widely known today as Kenmore.

In the second quarter of the nineteenth century, Fredericksburg was an emerging metropolis with a bustling economy, a new railroad, and a population totaling nearly 4,000 people. In his history of Fredericksburg, John Goolrick noted, “Government statistics show that there were in the town in 1840, seventy-three stores, two tanneries, one grist mill, two printing plants, four semi-weekly newspapers, five academies with 256 students, and seven schools with 165 scholars.”

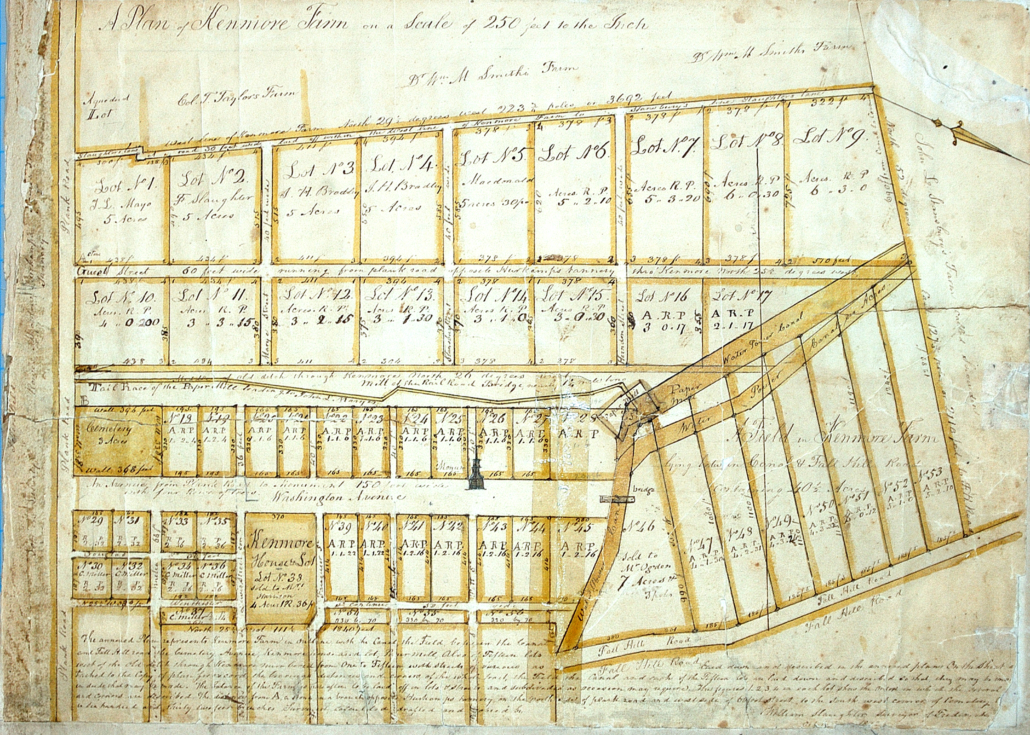

In 1859, 200 acres of Kenmore plantation, including the mansion house and the incomplete monument to Mary Washington, were sold to Franklin Slaughter. Slaughter promptly subdivided the land into 57 large lots divided by various streets and partnered with several investors to accommodate new suburban development (Figure 1). In addition to its lots, the Kenmore Farm plat depicts several early-nineteenth-century landscape features, including the Fredericksburg canal, a paper mill pond, and the mill’s race or tail, extending south along what is now Kenmore Avenue. Proprietors of the “Kenmore Company” were not as successful as they had hoped, but their subdivision of “Kenmore Farm” provided the general layout and street grid of College Terrace neighborhood.

During the 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg, Confederate troops held a stronghold along the heights around the city. The ground where the University of Mary Washington is situated was occupied by a Louisiana artillery unit commanded by a Lieutenant Landry. Confederate infantry held the base of the hill, and additional reserves occupied what is now College Avenue. Across the intervening valley (now the College Terrace neighborhood), the Union army occupied Fredericksburg, its advance elements taking positions along what was then the edge of town.

Not until December 13 did the Union troops begin a concerted push against Lee’s position. The artillerists on what is now the university campus were kept extremely busy that day. As the Union assault columns advanced toward Marye’s Heights several blocks to the south, the Confederate gunners fired into their exposed flanks. However, this action was not one sided though. The Confederate army also received counter battery fire from Union guns positioned across the valley around Kenmore [mansion]…. The main battle raged on December 13, but Union troops lay exposed on the cold ground dominated by Confederate guns on the 14th as well. On both days, Union skirmishers aggressively moved forward, taking shelter in the canal [paper mill raceway along Kenmore Avenue], as well as in a brick tannery on the south side of William Street at what is now Littlepage Street. The Fredericksburg Cemetery (established in 1844) provided cover for yet more riflemen. While the main Union attacks occurred several blocks to the south, the artillery from both sides fired obliquely across the front to either support or hinder the Federal columns…. A Mississippi soldier later wrote how Confederate cannon directed their fire into the Fredericksburg Cemetery to flush the Union infantry there…. Though the Union troops cleared the cemetery, their comrades maintained position in the canal and in the tannery. As the Mississippian remembered, the “large brick factory located in front of our right wing afforded them a vantage point which was quickly utilized by the enemy who fairly swarmed around it….”

In the end, the many days of killing did not change anything. Lee’s veterans still held the high ground, effectively blocking Burnside’s advance. Following their repulse at Fredericksburg, the Union forces withdrew.

Little development occurred in the neighborhood until after the war, although several lots continued to be sold within the Kenmore Farm subdivision. Fredericksburg merchant James H. Bradley purchased six 5-acre lots between May 1862 and September 1863 on either side of what is now Littlepage Street, and later erected that neighborhood’s oldest dwelling. Local tax records indicate that a small, plain house valued at $200 was built on the property between 1868 and 1869, although the land around it remained in agricultural and industrial use into the early twentieth century. The Bradley family’s farmhouse has expanded over time but remains extant at 1310 Littlepage Street.

Another important late-nineteenth-century feature of the neighborhood is Shiloh Cemetery, located at the corner of Littlepage and Monument Avenue. Soon after Shiloh Baptist Church trustees acquired the land in May 1882 from Absalom P. Rowe, some of the known graves from Potter’s field were moved to this new resting place. Others were moved during the construction of Maury School (originally Fredericksburg High School) between 1919 and 1920, and during the paving of Littlepage Street. The statue in the middle of the cemetery is dedicated to the unknown individuals removed during that period. Many prominent African Americans and former parishioners of the Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site), Shiloh Baptist Church (New Site), and the Mt. Zion Baptist Church are interred in this cemetery, including Joseph Walker and Jason C. Grant, for whom Walker-Grant Middle School is named, the Reverend B.H. Hester of the Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site), and the Reverend M. L. Murchison of the Shiloh Baptist Church (New Site).

Minor developments occurred on the lots fronting William Street in the late nineteenth century that are no longer extant, including a small gunpowder magazine built by the DuPont Company at the corner of Sunken Road. Another industrial remnant cannot be seen from the ground surface but survives below Kenmore Avenue where a brick flume channels water from the former paper mill to the Rappahannock River.

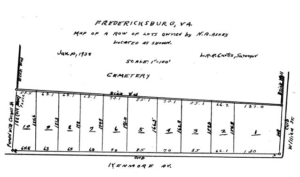

By the early twentieth century, the demand for suburban residential development had grown sufficiently to make lots within College Terrace a viable investment. In May 1916, James Bradley’s descendant sold much of their land to Frank Leighton Day (1868–1966), a professor of Bible and Philosophy at Randolph-Macon College in Ashland, Virginia. It remains to be known how Day came to connect with the Bradleys but it is clear that he and his wife never lived in Fredericksburg. Day named the new subdivision “College Terrace,” capitalizing on its proximity to the recently established State Normal and Industrial School for Women (now the University of Mary Washington). A plat created by Stuart Royer for Day in 1917, shows the subdivision bounded by Cornell Street on the south, Grove Avenue on the west, Kenmore Avenue (historically known as Weedon Street) on the east, and Sunken Road (then referred to as College Avenue) on the west (Figure 2).

The use of restrictive covenants on residential real estate is commonplace today but was just emerging as a legal tool for developers in the early twentieth century. Frank L. Day added several covenants to limit what could be done with the new lots in College Terrace, one of which was designed to prevent the sale of any lots to Black people (learn more about the history of racial covenants from UMW students’ website restrictedva.org). The deeds to each lot within Day’s subdivision included these restrictions for a period of 50 years from the date of sale:

- No lot shall be sold to people of African descent

- All lots shall be used exclusively for residential purposes. No dwelling unit shall be built costing less than $3,500

- No building shall be built closer than 60 feet to the concrete sidewalk on Guest Street (now Littlepage)

In the decades that followed, many lots from Slaughter’s subdivision of Kenmore Farm were further divided around College Terrace by area developers, real estate investors, banks, companies, and some smaller-scale builder/contractors. One of these new subdivisions also employed restrictive covenants by deed in an attempt to ensure a consistent physical appearance and White ownership (noted by an *). These new subdivisions around Day’s College Terrace included:

- Fredericksburg Homes, Inc. subdivision (1930) between Sunken and Littlepage north of William

- Heflin-Whitbeck (1931–1934) subdivision between Kenmore and Littlepage from Cornell to William

- Kenmore Division* (1931) comprises the north end of the neighborhood below the University’s athletic field

- N. A. Ashby’s subdivision (1938) on the east side of Kenmore between William and Cornell

- B. Lucas’ subdivision (1949) along the north side of Mary Ball Street

Known architects and builder-contractors who erected buildings within this neighborhood include:

- Andrew C. Garrison

- Blaine Lucas for Lucas Construction & Tyler Manufacturing

- Cecil L. Reid

- Elmer “Peck” Heflin

- Frank P. Stearns

- Fredericksburg Home Builders, Inc.

- H. H. Tyler

- W. H. Bell

Architectural features and styles commonly found in this neighborhood:

- Classical Revival

- Colonial Revival (Georgian, Federal, Dutch, and Tudor)

- Folk Victorian

- American Foursquare/Vernacular

- Craftsman/Bungalow

- Minimal Traditional/Cape Cod