HFFI is thrilled to be one of the Renwick’s biggest fans and hope you’ll join us in advocating for the high-quality preservation work it deserves!

Architectural Significance

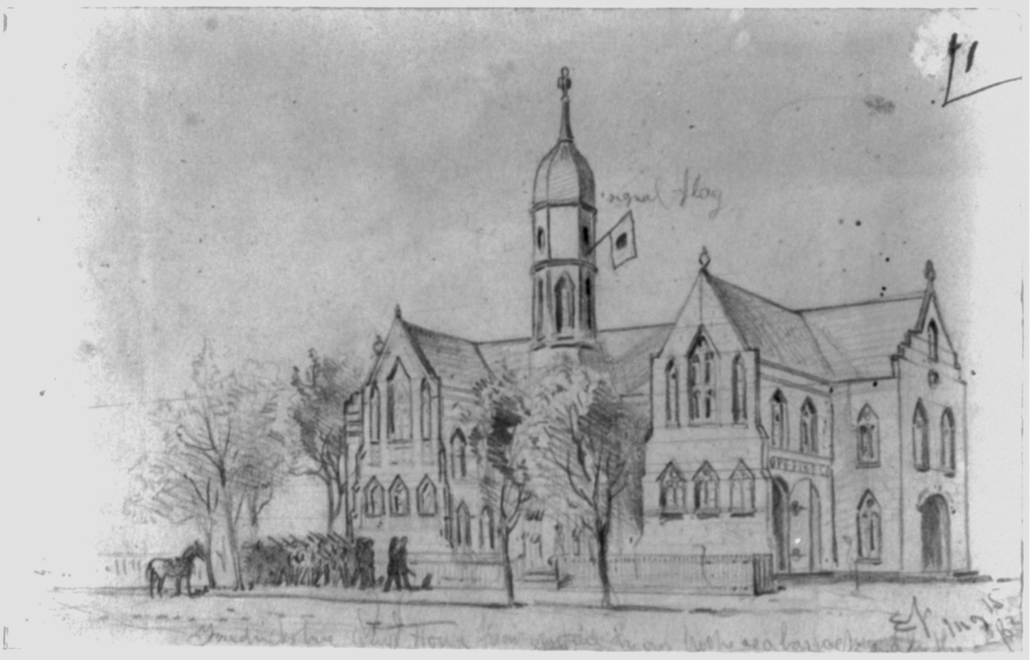

“Unique in Virginia and significant nationally is this pre-Civil War Gothic Revival Courthouse…. The building was controversial with the citizenry because of a tax levy, and Renwick responded with a simplified and economical Gothic Revival design, on a plan in the form of an E” (Wilson et al. 2002:306–308).

Authors of the City’s 2016 Historic Structures Report (HSR) on the Renwick complex noted that “The new Fredericksburg courthouse had the distinction of being the first civic building in Virginia to be constructed in the Gothic Revival style. Prominent exterior features of the style included lancet-shaped windows, many with wood tracery, and crow-stepped gable ends with parapets. The building’s polychromatic banding may have been the first appearance of such a feature in the country…. a bold design choice in 1852” (Green et al. 2016:2.15).

A 2014 dissertation written by Nicholas Genau, an Art History student at the University of Virginia and Doctorate candidate, entitled Inventing Architectural Identity: The Institutional Architecture of James Renwick, Jr., 1818-95, examined the architect’s prolific career and identified more than 125 projects with “significant evidence or at least one mention in a major professional publication” credited to him—just one of which is a courthouse (Genau 2014:222–232). At a time when “American designers were beginning to search for more eclectic expressions in the built form… Renwick’s eclecticism offered those groups and institutions powerful architectural identities that have become symbolic to their respective personalities even in the twenty-first century” (Genau 2014:220). The sheer volume of Renwick’s work illustrates his popularity and influence, yet few architectural documents and primary sources survive to give insight into his contributions as an exemplar of medieval revivalism in American architecture. While Renwick “designed an unparalleled number of building types, of which the most prominent are churches, commercial buildings, asylums, and museums,” many have been lost “to the ever-changing fabric of the metropolitan centers” in which they were constructed (Genau 2014:17). His most frequently praised designs (Grace Church and St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City, and the Smithsonian and Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C.) were produced for prestigious patrons and are, therefore, the most documented.

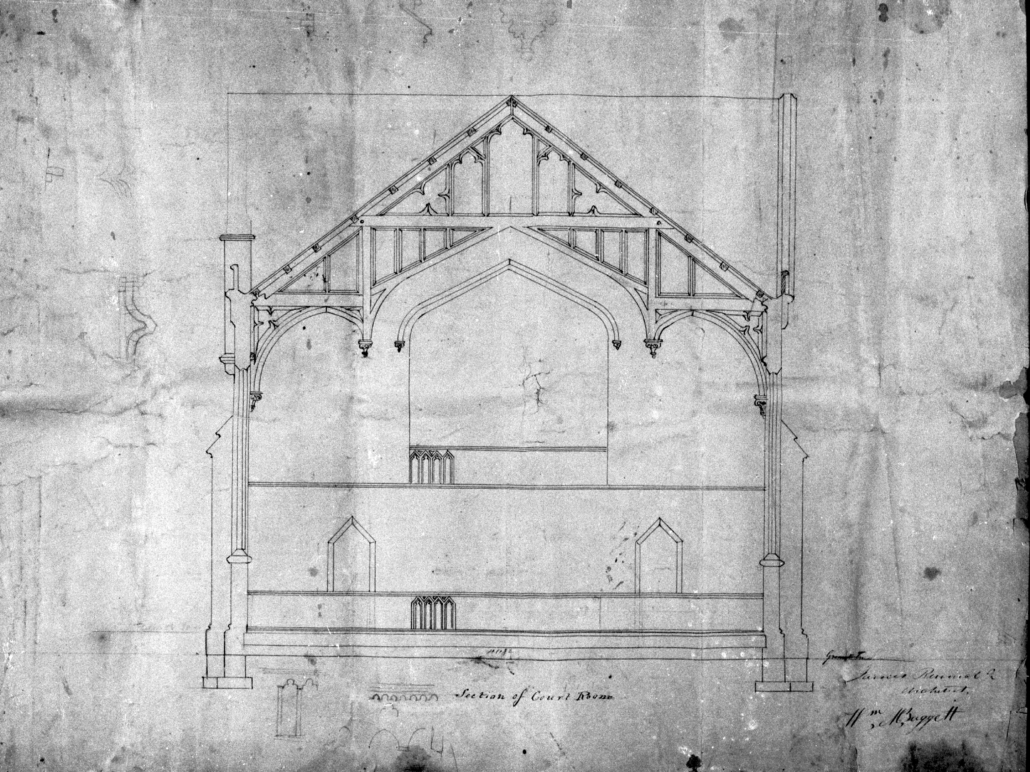

Selma Rattner (1929-2005), an acclaimed architectural historian, preservationist, and unofficial biographer of the architect James Renwick, Jr., wrote her 1977 master’s thesis at Columbia on Grace Church and Gothic Revival architecture in the United States. She also “lectured and published on him throughout the 1970s and 1980s,” researching “Renwick’s minor, and in some cases virtually unknown works, traveling often to visit libraries, archives, museums, and building sites” (Columbia Universities Libraries 2023). During this work, Rattner “amassed a significant amount of primary and secondary research material over more than three decades” that is now part of the Avery Drawings & Archives Collections at Columbia University. Two courthouse designs appear within Rattner’s collection: one never left the drawing room table while the other stands tall at the center of Fredericksburg, Virginia.

Learn more about James Renwick, Jr., (1818-1895) and his architecture:

- “James Renwick, Jr., Architect of Smithsonian Buildings,” Stories from the Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institute. https://siarchives.si.edu/history/featured-topics/stories/james-renwick-jr-architect-smithsonian-buildings

- Robert D. Owen. 1849. “Hints on Public Architecture” with drawings by James Renwick, Jr. https://archive.org/details/hintsonpublicar01owengoog/page/n3/mode/2up

- Apmann, Sarah Bean. 2018. “James Renwick, Jr., 19th Century Architect Extraordinaire!,” Off the Grid: Village Preservation Blog. https://www.villagepreservation.org/2018/11/09/james-renwick-jr-19th-century-architect-extraordinaire/

Civil War Significance

A pivotal strategic asset throughout the Battle(s) of Fredericksburg and the Civil War, the Renwick Courthouse served as a temporary holding cell, communication tower, hospital, and symbolic icon in the occupied City. As the center of local government, it was also the place where many debates and notable events leading up to the conflict occurred, including local leaders’ vote to join the governor and state legislators in the decision to cede from the Union on May 23, 1861.

Learn more about what happened at the Courthouse during the Civil War:

- Hennessey, John. 2011. “The secession vote, part 1: the lament of Judge Lomax, May 23, 1861,” Fredericksburg Remembered. https://fredericksburghistory.wordpress.com/2011/05/23/the-lament-of-judge-lomax-may-23-1861-part-1/

Reconstruction and the Courthouse

15 December 1865—Granted permission to hold Freedman’s Court in a Courthouse room.

15 February 1866—Young Men’s Literary Society allowed to use Courthouse hall for evening meetings.

22 August 1871—Appropriated $400 to “fit up” the south wing of the Courthouse for use of the public

schools.

24 and 31 September 1872—Courthouse to be open for public meetings with approval of the Mayor and

with payment for gas and cleaning.

11 December 1876—Library Association authorized to use a room in the Courthouse for a library.

21 August 1885—Granted permission to use the District Courtroom for a high grade school.

1 July 1887—Shiloh Baptist Church asked to continue to occupy the courthouse for a little longer—until

a new building could be procured. (Church history says that the church met in the Courthouse for nearly a

year after the church’s building collapsed in 1886 due to flood damage.)